The Hunt for Tavaputs

Spectacular skies, off-road adventures and abundant wildlife in remote central Utah

If I didn’t feel my feet firmly grounded beneath me, it’d be tempting to imagine I’m floating in space. Suspended upside down in a bowl of stars, the entire universe of millions of points of light piercing the dark pre-dawn sky.

Even the slightest noise carries in the bone-dry atmosphere on this chilly fall morning. A whisper of wind through aspens, the low blow and snort from horses corralled on the ridgeline above us; the faint creak and rustle of my sons pulling on jackets and lacing up their boots inside the cabin behind me. It’s a stark and magical moment on the isolated West Tavaputs Plateau in southeast Utah’s Carbon County, in the cold early hours before Tavaputs Ranch owner Butch Jensen turns on the generator for the day, the only source of power in this remote ranch. But between ten at night and five-thirty in the morning, the plateau is reclaimed in still velvet darkness and the persistence of moonlight and brilliant stars. It’s a serious and magical dose of humility and wonder to start the day.

The crunch of boots on the frosted grass blades are the only sound my family makes as we head to the main lodge, the path from our cabin lit only by a quarter moon and the headlamp my oldest son, Connor (16), carries pointed down at the ground by his side so our eyes stay adjusted to the dark. Every exhale pours over our heads in the form of cloudy nimbuses, evident with the slightest exertion at nearly 10,000 feet.

"But between ten at night and five-thirty in the morning, the plateau is reclaimed in still velvet darkness and the persistence of moonlight and brilliant stars. It’s a serious and magical dose of humility and wonder to start the day."

Two sets of glowing eyes reveal a couple of the ranch’s border collie puppies scampering toward us (Read: Canine Crew of Tavaputs Ranch). I mentally mark where they came from on the edge of the clearing, hoping that’s where we’ll find one of my husband Mike’s boots the pups made off with the night before from the cabin porch (pro tip: bring an old towel to stack your muddy boots on inside – they’ll stay warm, dry and safe from puppy predation). Gazing down the dark stretch of Desolation Canyon, nine miles away the Green River winds thousands of feet below in wily bends, which Butch Jensen recommended we raft given the chance. “There are nice rapids every day, but they’re not the killing kind.”

Giving some gravitas to the legend that the name Tavaputs means “sunrise” in the Ute language, the first rays of sunlight on the horizon paint the canyon in vivid colors. The distant glow of lights on the eastern horizon come from the community of Vernal, but they’re gradually taken over by the sun rising against a sky filled with brilliant orange, pink and violet tinged clouds.

The guest in the cabin next door told me yesterday that he leaves one of the lamps switched “on” overnight as an automatic alarm clock. “As soon as the Jensens get the generator going,” he advised me, “you know that Jeanie already has the coffee made.” Our youngest son, Garrett (13), is jumping the gun (so to speak) this morning at Tavaputs, eager to eat breakfast and head out with hunting guide Kenny Gunter to track the ever-moving elk herds and prepare for the day, long before shots can be legally fired at first light. Honestly, I’m more motivated by the opportunity to fill up a mug with invigorating ranch coffee poured from the giant stainless steel percolators in the ranch kitchen.

The Many Moving Parts of a Working Ranch

Unlike the rest of my family, who immediately head out to scout elk with Gunter, I have the luxury of another cup of coffee and some time spent catching up with ranch owner Jeanie Wilcox Jensen, her daughter Jennie Christensen and Jennie’s adorable sons, Jax (5) and Jett (3). We’re visiting the ranch at a very special and busy time of year, as the Jensens are readying their cattle for the fall roundup. In addition to my family of four and one other muzzleloader mule deer hunter, all of the dozen-plus ranch guests are family or long-time friends of the Jensens. Along with 10 hired cowboys, the guests pitch in gratis to assist the Jensen’s crew with moving cattle from the plateau over 3,000 feet down Sheep Canyon road to Range Creek and on to the Jensen’s winter range. Friends Gail and Steve Enslinger have hauled themselves and their horses from Tennessee each fall to help with roundup since 2011. “We wouldn’t miss it,” says Gail. “There’s nothing like this place in the world, and the Jensens are absolutely the best people. We’re blessed to be here.”

Jeanie’s ancestors started raising cattle in Desolation Canyon in 1887, making her a fifth generation rancher in Utah. Her family built livestock trails up to the isolated plateau, and mules and horses packed in everything until the first road was built in 1943. Butch’s family started ranching in the area in the early 20th century, and Butch grew up on a ranch adjoining Jeanie’s. Butch and Jeanie laughingly told me that they’d spent their childhood years as friends and neighbors, riding stick horses when they were little and helping each other’s families in the saddle during roundups. Their courtship began in earnest, however, when Butch curtailed his college studies in 1971 to start cowboying full time at the T.N. Ranch. Butch and Jeanie’s first date was a picnic at the old Wilcox ranch (now home to the University of Utah’s Range Creek Archaeological Field School). They married in 1978 and combined the family ranches in 1999. They now oversee about 10,000 private acres and an additional 200,000 acres of federal and state leases. Fundamentally a working ranch, the current Tavaputs operation manages two herds of more than 1,200 cattle.

Back in the 1950s, Jeanie Jensen’s parents Don and Jeannette Wilcox sought to diversify the ranch’s income by inviting guests to experience the remote plateau during hunting season, making Tavaputs the oldest continually run family guest ranch in Utah. On the neighboring T.N. Ranch, Butch started guiding mule deer hunts by the time he was fourteen. Tavaputs Ranch further expanded their guest operation in the 1970s to summer visitors, adding trail rides and wildlife viewing activities. Currently, the ranch can accommodate up to thirty-five visitors at a time during the June–September season, and all meals are included.

Over the years, crews of wildland firefighters staked out on the plateau have also been grateful for the Jensen’s hospitality. “Cooking for 300-plus firefighters was quite an experience; they are such polite, grateful and extremely hard-working folks,” praised Jeanie. My husband and I can attest that those smoke-hounds probably had the best meals of their career eating at Tavaputs Ranch; we certainly never had meals that good during our three seasons of wildland firefighting. During one fire, Jeanie, Jennie and a few helpers made hearty breakfasts, planned massive dinners and packed 600 sandwiches every day. Says Jeanie, “They would come back for at least seconds” — a fire camp luxury — “and I can say we never ran out of food. We must have had a guardian angel looking over our kitchen work!”

As Jeanie refills our coffee mugs, young Jax and Jett are getting ready to “help” with the cattle drive, pulling on their tiny leather chaps and boots in the main lodge dining room. They show me their engraved spurs, handmade by their father, Jeff Christensen, who has already headed out to saddle their horses for the long day ahead. Happy to pitch in, I cut up some more cantaloupe by request for Jett, encourage the boys to finish their scrambled eggs, and spread some toast with elderberry jam homemade by Kenny Gunter’s wife from fruit collected at the ranch.

"It’s kind of a very challenging modern-day treasure hunt, where finding 'x' brings you to one of the most beautiful spots on the planet, and you’re rewarded with a warm smile and hearty meal."

The dining room of the main lodge is imbued with the rich history of the area: family photographs line the walls, and under the glass on every table are newspaper and magazine clippings featuring the ranch. There are apocryphal tales of cattle rustlers, and Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch legendarily hiding out under the averted eyes of Jeanie’s great-granddad, Jim McPherson. Other articles chronicle the Jensens’ prestigious national rangeland stewardship awards.

In 2009, Tavaputs Ranch won the Leopold Conservation Award, for which they were nominated based upon their commitment to “the best practices of modern ranching with the best traditions of the West, with hospitality a given, education a goal and increasing the strength and vitality of agriculture in Utah the result.” Butch and Jeanie’s son Tate Jensen, who passed away in 2011, is widely remembered for his leadership in Utah rangeland conservation and progressive stewardship practices. Alongside his father Butch, Tate’s conservation work was instrumental in Tavaputs being awarded the National Cattlemen Environmental Stewardship Award in 2010, a legacy that continues in Tavaputs Ranch operations policy today.

Providing their future generations a healthy and productive rangeland is a major priority for the Jensens. “I’m so glad we can raise our boys on the ranch, just like I was taught,” says Jennie Christensen. “It’s a way of life that’s disappearing.”

Meanwhile, little Jax Christensen is telling me all about the roundup in minute detail: He’ll be riding his horse named Smoke, and his younger brother Jett will ride Red Moon all day. He tells me which brands belong to his Nana, his momma and other family members. Says Jennie, “I registered the boys’ brands with the state as soon as they were born,” and the state registrar told her those were the youngest brand-owners they’d ever seen. Jax tells me the cattle will be moved across the plateau to specific areas in preparation for the big trail ride, saying of his grandmother’s cattle, “Nan keeps some Brahmas and longhorn crosses; they’re the best ones for leading cows on the trail,” underscoring the fact that this charming five-year-old already has thousands of acres of geography that he’s committed to spatial memory and ranching knowledge that I can’t even begin to comprehend.

Butch and Jeanie are the epitome of proud grandparents, answering a barrage of questions from the boys with a patient grin. Although Butch Jensen may look like a tough-as-nails rancher, over the years of knowing him I’ve come to the conclusion he’s a big softie, whether it’s caring for injured animals or accommodating his precocious grandsons. “My proudest moments are spent with my grandkids,” he tells me. Especially when he’s out with them riding the range.

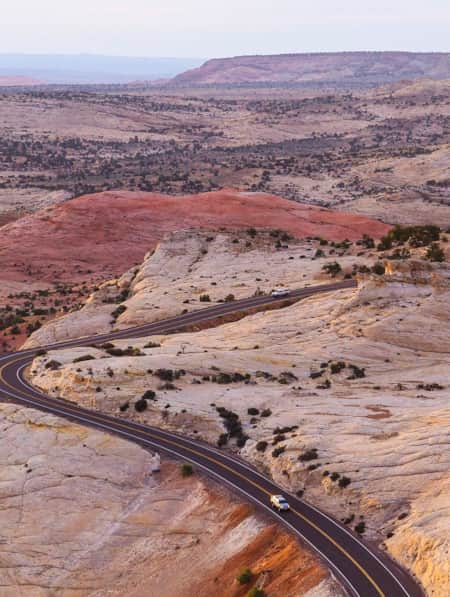

Remote, Wild, Life

Although the Jensen’s have curtailed offering horseback trail rides due to liability concerns, that’s not to say a visit to the ranch is without challenge. Ranch guests no longer have to come in by mule or horseback, however accessing the isolated ranch is formidable trek even today. For a fee, the Jensens do provide shuttle service from nearby Sunnyside, and there is prop airplane service available through a local aviation contractor in the town of Green River. But driving up to the plateau in our own pickup truck is an experience my boys think is one of the best parts of getting to Tavaputs. When you book a trip to the ranch, you’re sent an email with directions to a local market at the base of an access road. There, you sign for an envelope, which contains a key for the many ranch gates and a full page of step-by-step directions. Depending on weather and road conditions, the approach takes over an hour, ascends over a thousand feet in elevation, requires high clearance, some bits of 4WD creativity on muddy or snowy days, and minute attention to the various road turnoffs. It’s kind of a very challenging modern-day treasure hunt, where finding “x” brings you to one of the most beautiful spots on the planet, and you’re rewarded with a warm smile and hearty meal. After a particularly perilous snowstorm this trip, the glug of Crown Royal added to my coffee from another guest’s BYOB was icing on the cake.

But that’s not to say that any experience this far from modern comforts comes without significant risk. The nearest hospital is 45 minutes away — by helicopter.

Most visits, however, are relatively free from situational panic. Visitors to the ranch enjoy bird watching, hiking on the plateau and down Desolation Canyon to visit the old spring house and homestead ruins, or tour the significant Fremont archaeological sites of Range Creek with guides under permit from the Natural History Museum of Utah. Last year, the Jensens started offering ATV tours of the ranch, rated “novice,” which have become so popular they need to be booked months in advance. Healthy and thriving populations of greater sage grouse, mule deer, black bear, mountain lion and wild turkey abound. In 1981, Butch and Jeanie’s fathers worked together to request and coordinate a Rocky Mountain elk relocation program on the plateau. Now, the Tavaputs plateau is home to over 1,600 head of elk, with plenty of opportunities to see trophy-class bulls in the herd. Like many ranchers, the Jensens continue to rely on revenue from guided hunts to bring in consistent income during lean years resulting from bad weather or drops in beef prices. “Even with big numbers of elk, they aren’t a conflict with grazing cattle,” says Butch Jensen. “There’s enough healthy vegetation for all of them.”

You’ll even spot the occasional moose, as I was surprised to see on my first visit years ago. Butch Jensen tells me, “The DWR sends their ‘problem moose’ from the Wasatch our way. We’re glad to have them,” as they’re a surprise and delight for visitors. According to Utah Department of Wildlife (DWR) biologist Brad Crompton, who has worked out of the nearby Price division office for over 20 years, many of those “problem moose” have been relocated from urban interface areas, especially golf courses. Says Crompton, “The moose don’t have anywhere to get into trouble on the plateau.” And Crompton describes Range Creek below the Tavaputs plateau as a fantastic drainage for diversity, noting that a handful of beaver have already helped improve erosion after wildfires in the area. He continues, “Butch and Jeanie balance cattle ranching while also encouraging wildlife,” and they’ve done so very well.

“From a wildlife perspective,” says Crompton, “the West Tavaputs Plateau is so amazing and geographically unique,” with the plateau’s narrow band only a mile or two wide, and the terrain steeply plummeting thousands of feet down on either side. Crompton describes the plateau as having very healthy spruce, aspen and grass communities, providing abundant forage for wildlife: “Food, water and cover. They’re crucial for sage grouse and so many other species,” and Crompton emphasized that keeping good working relationships between land management agencies and livestock operators is crucial to ecosystem health whether on private or public land.

“It’s my favorite spot in the state,” Crompton told me. “The West Tavaputs Plateau — it’s way cool up there.”

For many visitors to Tavaputs Ranch, it is this sustained ranch ecosystem alone that defines the visit: something more relaxed, unplugged and built around social interactions with the staff or those quiet evenings under the stars. For others, the wide-open plateau and multiplying canyons offer another experience, and one equally attune to nature.

Hunting the Range: Expert Tavaputs

Our family first met the extended Jensen bunch in 2013, after Mike and I won a live-auction bid at the Natural History Museum of Utah annual gala for a weekend at Tavaputs Ranch and a Range Creek archaeological tour. During our initial visit, the area received torrential record-breaking rainfall, which in rather dramatic fashion washed out road access to Range Creek. We spent the socked-in weekend getting to know the Jensens and literally breaking bread together over many delicious meals spent waiting for the skies to clear. During the brief breaks in the downpour, we hiked a bit down Desolation Canyon and went on a slip-sliding Jeep tour with Butch around the ranch. My then-young sons loved nothing more than sitting on the floor of the lodge with toddler Jax for hours, playing games, coloring and having Jax direct them in building extensive corrals and pastures with the Jensens’ vast collection of toy barns, cattle, horses and hauler trucks.

"It’s a constant and quiet level of vigilance and observation, whether we’re on an active hunt or on a day hike in a national park."

The Jensens invited us to come back after the Sheep Canyon road re-opened a few weeks later, and we were able to experience the wonders of Range Creek’s extensive cultural history at last (Read: Spirits in the Rock). Over the years, our families have kept in touch through social media and holiday cards. We had lengthy phone conversations when I interviewed Jeanie for a Utah food magazine article about traditional ranch recipes, and a couple of years ago I wrote a biographical statement for Butch when he was recognized by the National Cattlemen’s Association. From the outside, it might seem like my transitory urban-liberal family wouldn’t have much in common with the Jensen’s multi-generational rural life in the heart of Utah ranch country. But the values that we share — hard work, time spent outdoors, appreciation for family and good food — turned out to be a common foundation for friendship over the years. Our later visit coincided with hunting season at Tavaputs, and my sons loved nothing more than hearing tales from the field over dinner and seeing the huge record-breaking elk and mule deer brought in by hunters travelling to Tavaputs from all over the country. Already experienced small game and waterfowl hunters, my boys dreamed of going on their own Tavaputs hunt some day, and were beyond thrilled when we gifted Garrett with a cow elk hunt to commemorate his becoming a teenager.

Our family’s journey leading to a hunt at Tavaputs in many ways reverses the national trajectory of hunting demographics, which have declined steadily since the 1950s. Prior to World War II, with the exception of urban areas, most Americans grew up hunting and it was a multi-generational family activity. My mother went bow hunting alongside her parents, but it wasn’t something that was a big part of my own childhood with the exception of plinking cans and exterminating “varmits” with a 22-pump action rifle on my grandparents’ farm in Indiana. And both Mike and I grew up in families where the occasional car-camping trip was of the established campground variety.

We met in the 1990s when we were backcountry rangers and wildland firefighters for the U.S. Forest Service near Mount Rainier, Washington, and our love for the outdoors has continued over the years even as we added mortgages, dogs and eventually human progeny to the mix. And working and traveling all over the mountains of the western United States went hand-in-hand for us with a burgeoning obsession with fly-fishing. Raising competent and conscientious outdoorsmen has always been a parenting priority, as well. Our children came along on our backcountry adventures since they could sit up in a backpack, and their innate curiosity about wildlife, the natural food chain and our place as human consumers in it brought us full circle to hunting. And it also appealed to me as a way for us to source our own protein in the form of free-range, organic meat. As former USFS wilderness rangers, Mike and I are passionate about wildlife conservation and adamantly by-the-book regarding gun safety and hunter education. Both of us registered for hunters safety classes alongside each of our boys when they became old enough to handle firearms safely.

We’re feeling more than a little spoiled having Garrett go after his first elk tag in the 95 percent success rate of the guided environment at Tavaputs, with hot beverages in a thermos heading out, a hearty meal (which I don’t have to prepare) and warm shower to look forward to at the end of the day. Usually, we’re camped in our pop-up trailer or backpacking in to the designated hunting unit on public land, ready to carry out the quartered game in backpacks if the hunt is successful. And if we’re really lucky, that trek is mostly downhill back to the truck.

Having worked for fifteen years at Tavaputs as a ranch cowboy and hunting guide, Kenny Gunter can anticipate where he’ll be able to track elk with Garrett’s legal tag requirements, but there’s no little amount of serendipity and hard work still involved. Intangibles like the weather, vegetation coverage and the herd-specific dynamics of each group of animals means that there’s still quite a bit of time spent hiking and scouting through binoculars or a long-range scope. Before Garrett eventually harvested his elk with a 258-yard shot, he’d hiked 12 miles over two days in the mountainous terrain, time almost entirely spent with a big grin on his face.

It’s a rejuvenating and grounding experience for us all at Tavaputs, whether we’re on the trail or at the ranch house, especially in the fall. Learning to hunt at the wry old age of 40, Mike believes the way he experiences the outdoors has completely changed. “Everything matters,” he says. It’s a much more intense and visceral series of movements. Compared to mountain biking, where the focus is almost entirely in the narrow window of the trail immediately in front, or hiking and backpacking motivated by moving on a path with a particular destination in mind, hunting forces us to slow down. Be in the moment. Explains Mike, “I’m not walking over the landscape; I’m part of it. Now, all of my senses are continually engaged in a way that they never were when I was just hiking an established trail.” The direction of the wind, its speed, how the clouds are moving or building up, even the smallest shifts in weather patterns influence animal movement. During the Tavaputs hunt, Mike said he smelled the elk herd long before they heard or saw it. “Before, I would see an animal track, briefly look at it to identify species and keep moving,” Mike says. “Now, I’m looking at that track from a completely different perspective. Not just what type of animal, but how big is it, in which direction is it moving and how fast. How long ago was it made?”

A lot of time hunting is spent being still, looking through binoculars or a scope and reading the landscape writ large. And this investigation goes beyond looking for whatever we may be carrying a tag for: The whole landscape is teeming with activity. Predators large and small all have interactions with the land, and we now see our place as a factor in this dynamic like we never did hiking. And it adds an entirely new and deeper communication between us as parents with our boys as we experience the outdoors. As they’ve grown as hunters themselves, this perspective is reflexive and ingrained in them from the start. It’s a constant and quiet level of vigilance and observation, whether we’re on an active hunt or on a day hike in a national park. Each trip is an opportunity to learn more about that specific environment and its inhabitants. Everything slows down for a bit. We spend more time watching quietly and listening intently. We’re quiet because we need to be.

For culinary dabblers like me, knowing exactly where our meat comes from and how it is processed from the very start imbues the entire experience with respect for the animal in a very primal way (Read: Where's the Meat?). And very little meat is wasted during processing, which at Tavaputs Ranch happens on the deck next to their cold storage facility so that we can load up the gigantic coolers in our truck with quartered elk the morning we head home. And guide Kenny Gunter graciously offers to soak the liver and heart overnight in salt water if I’d like to take it (that’d be a hell yes, Kenny).

After we return home, it takes about six hours for Mike and I to break down the elk into primal cuts. I make three different kinds of sausage from the trim, sauté the elk liver with bacon fat, cognac and onions to make a silky pâté, and ended up curing and smoking the heart, dusted with black peppercorn and coriander, pastrami-style. I roast the bones with vegetable scraps and then simmer it all for hours to make quarts of rich elk stock, stacked in wide-mouthed jars in the freezer for future meals of stew or onion soup.

But aside from the delicious outcome of the hunt that will feed our family all winter long, it’s those moments of being in the outdoors with my family at Tavaputs that I treasure most, far from traffic and crowds and searching for wifi signals, getting lost in a starry sky.

Central Utah

-

Base Camp Green River

It’s time to leave the city and the suburbs behind and drive through the mountains and canyons into the Utah desert. True, Green River is barely an hour away from Arches and Canyonlands national parks, so those are options to extend your 3-day trip. But for this itinerary, we’re focusing on the local secrets: the hidden labyrinth of slot canyons and whimsical hoodoos of the San Rafael Swell and the dining and heritage that are part of the unique fabric of Green River.

-

Huntington State Park

Enjoy leisurely hikes, a beach, grassy campgrounds and the opportunity to fish morning, noon and night — or use as a base camp to hiking and riding the San Rafael Swell and Manti-La Sal National Forest.

-

Price

Price sits close to the northern section of the San Rafael Swell, which is home to vast deserts, yawning canyons, and fascinating rock formations. The area is known for its coal mining, as well as its recreational opportunities.