Spirits in the Rock

Ancient Peoples and the Modern Traveler in Remote Range Creek Canyon

“We call it Choo-Choo Rock,” says Butch Jensen, our Range Creek Canyon guide for the day, as he points to the distinctive landmark. He’s the owner of Tavaputs Ranch, located on the plateau looming thousands of feet above us (Read: The Hunt for Tavaputs). Butch continues, “It’s Locomotive Rock to everyone else, but that’s what Jeanie has called it since she was a little girl,” and the name has stuck for the Jensen family. He’s referring to his wife of almost four decades, Jeanie Wilcox Jensen, who along with her parents and the four generations of ranchers before her grew up exploring the nooks and crannies of Range Creek’s spectacular and unforgiving landscape near the Book Cliffs in southeast Utah. In 2001, Jeanie’s uncle Waldo Wilcox sold the Range Creek ranch property to a trust; in turn the land is now owned and protected by the state of Utah and the Natural History Museum of Utah.

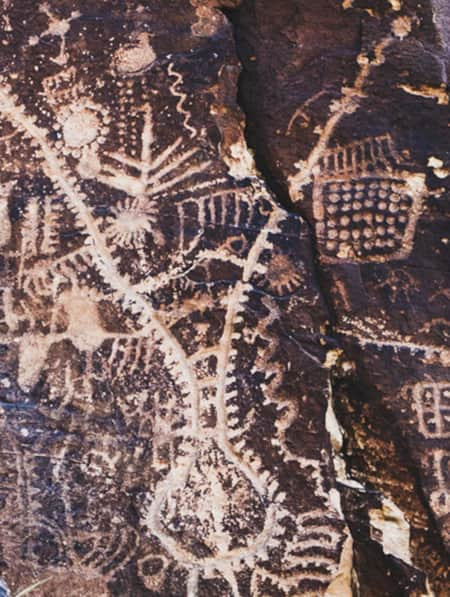

Range Creek is also home to some of the richest undisturbed remains of Fremont native culture in the southwest, including spectacular pictograph and petroglyph panels and ancient food storage granaries tucked into precarious cliff faces.

"The road itself is a celebration of cowboy engineering and the judicious use of dynamite; in most cases a one-lane dirt path blasted into the rocky cliff face."

Descending into Range Creek from the West Tavaputs Plateau is part of the adventure. The Wilcoxes built Sheep Canyon Road in 1951–52, the almost completely vertical three thousand-foot drop sliced by ten switchbacks. It’s easily maneuvered in a high-clearance Jeep, but vehicles any longer than that — like the Suburbans the Jensens use for larger tour groups — need to complete a couple of K-turns on the steeply angled pitch. The road itself is a celebration of cowboy engineering and the judicious use of dynamite; in most cases a one-lane dirt path blasted into the rocky cliff face. It’s a drive that’s equal parts visually stunning and hold-your-breath terrifying, especially in bad weather.

“After we hit the first switchback, things can get pretty quiet on the ride,” says Butch of passengers on their first Sheep Canyon experience, “There’ve been some white knuckles.” Understatement, thy name is Butch Jensen.

In Search of Prehistory

For visitors who may have experienced Ancestral Puebloan architecture like that found at Mesa Verde or Chaco Canyon, the Fremont remains in Range Creek Canyon are difficult to spot immediately. They’re subtle linear structures that blend into the sedimentary-layered cliff bands, or scrub-covered circular stone rings indicating where pit houses once stood. The Jensens help guests pick out the ingeniously camouflaged granaries — stacked rock food storage silos mortared with mud carried up hundreds of feet from the creek bottom below — by setting up spotting scopes aligned with the features, something they can do easily after a lifetime of spying the sites with the naked eye.

On sunny days, Butch will pull out what he calls his “cowboy laser pointer,” a small mirror to shine up onto painted pictograph panels to help visitors pinpoint their location. Once he’s given a visual nudge or two, it becomes easier for guests to pick up the features through binoculars.

Tucked under overhanging ledges and clinging impossibly to cliff faces, it’s a testament to the fierce determination of the canyon’s early inhabitants to secure defensible food storage. Even accounting for erosion over hundreds of years since they were built, the granaries are constructed in precarious locations, most only accessible in modern times by highly trained, rock-climbing archaeologists who rappel from the crumbling plateau tops down to the ancient remains.

Butch Jensen pulls out a three-ring binder packed with neatly organized photographs and magazine articles illustrating close-ups of the sites we’ve spied with our binoculars. Piles of corn cobs the size of a man’s thumb are stacked in one corner of a granary, guarded by a large red human-figured pictograph painted on the sheer rock face adjacent. Time and the elements have erased many signs of ancient access to the sites, whether by ladders, ropes or hand-and-toe-holds chiseled into the rock face. The inaccessibility of the sites is a boon and a curse to archaeologists searching for clues about why the Fremont precipitously left the canyon before 1200 A.D. Butch points with his cowboy laser to a spot just above a granary on a flat saddle connecting two ridge tops that archaeologists dubbed the “deluxe apartment in the sky.” Says Jensen, “There are remains of some pit houses up there, and when you climb up, there’s only one crack in the ledge that you can follow to access it or you’ll miss getting up there. There’s still a pile of rocks stacked up at the top, like they’d collected them for defensive protection."

My inner mama-bear shudders to think of raising toddlers on the knife-edge ridge tops, with sheer drop-offs on either side of the small group of pit houses built hundreds of feet above the creek bottom. Was it desperation and self-protection that drove the Fremont to live so perilously? Or a desire to be closer to the elements, their gods or the powerful sky?

Archaeologists studying the settlement patterns of Range Creek and other nearby drainages note that early inhabitants of the areas cultivated crops in the creek bottoms and built settlements nearby on gentle slopes above the flood zone. Over time, the Fremont moved higher up the cliff faces for both living and for storing food, perhaps as a defensive measure against raiding. Says NHMU archaeologist and field school director Shannon Boomgarden, “It’s all a very tight occupation period.” Although there are indicators of people in the area as early as 400 A.D., the vast majority of the artifact concentrations and architecture (which can be dated by the wood beams used in construction of dwellings and granaries) points to peak occupation between 900-1200 A.D.

"My inner mama-bear shudders to think of raising toddlers on the knife-edge ridge tops ... hundreds of feet above the creek bottom."

Since 1999, a dozen or so students enrolled each summer for the Range Creek archaeological field school have been annually inventorying the known sites in the canyon, monitoring for vandalism — which is fortunately rare with the limited access to the canyon and current permitting system — and erosion. They conduct research projects in the canyon mimicking prehistoric agricultural strategies to figure out just how much work and resources it took for people to irrigate, grow, harvest, then transport their crops to the remote granaries.

Says Boomgarden, “It’s an incredible opportunity for research,” in Range Creek Canyon. “I love that students are so isolated in this spot,” with no internet access, cell phones or outside distractions; all communication in the canyon is done face-to-face. “It’s a good baseline to come from when thinking about how the Fremont lived. It’s valuable for students to take a moment to image what it was like a thousand years ago.”

As we pile into Butch’s Jeep for our return trip up to the Tavaputs Plateau, I’m struck anew by the intimacy and challenging verticality of this landscape, how this rugged and intimidating place has changed through time, from the Fremont living precariously on ridge tops to the Wilcox family literally building access to the world with dynamite and cowboy ingenuity. And I give my kids a big huge mama-bear hug when I meet them back at the ranch, thankful for toddler years spent on terra firma.

When You Go

- Access to Tavaputs Ranch and Range Creek Canyon is via steep, narrow unimproved roads, which may be impassible when wet. High clearance vehicles required, 4WD highly recommended.

- Permits available May 15th to November 30th, subject to road and weather conditions.

- Summertime temperatures in the canyon typically exceed 100 degrees, although mornings and evening temps can be quite cool. Unexpected rain showers are common. Dress appropriately with rugged closed-toe shoes and breathable layers. Bring a hat and sunscreen.

- No food, potable water or other services are available in the canyon, except for guests at Tavaputs Ranch. There is no fuel service or cell phone coverage in Range Creek Canyon or on the Tavaputs Plateau.

- It is unlawful for any person to intentionally alter, remove, injure or destroy archaeological and historic sites.

- Tread lightly and take only photographs. Artifacts should remain where they were found.

- If you witness illegal activity, protect our heritage by reporting incidents to the appropriate authorities.

- Range Creek is black bear country. Keep a clean camp and store food items in vehicles when not in use.