Reef Walking, Petroglyphs and Bones

A journey through the rugged and wonderful San Rafael Swell and heritage-rich Nine Mile Canyon

Much of Central Utah feels completely free-form. It is a place that invites both exploration and interpretation. It is a place where questions are many and answers are elusive.

Yet there are exposed secrets everywhere. These secrets seem to unify my exploration from Nine Mile Canyon through the San Rafael Swell. Prehistoric cultures left messages on the walls of geologically fantastic places — places that today remain seldom trafficked by modern cultures. When it comes to interpreting the messages, in many ways, we can only guess.

Drop back another 150 million years when inland seas swept across muddy plains, and a floodplain hardened into the most prolific source of dinosaur fossils on the continent: the Morrison Formation. Scientists cannot agree what the climate was like at the time. But paleontologists crack open the rock — scraping away limestone or splitting sheets of shale — and they reveal new passages from the Earth’s history. The rock does tell stories. (Read: "A Deep Dig into Utah’s Deep Time")

The World's Densest Concentration of Dinosaur Bones

When I see the sign for Emery County, I pull off to the side of the road and draw in a deep breath. On visits to the area when my mom was young, her dad used to get out at the Emery County line and comment on the clean country air. So, grandpa, this one’s for you.

Driving to the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry means following several miles of well-maintained, but unpaved, road due east of Central Utah’s Route 10. The road rises, falls and winds through the San Rafael Swell topography, continually shifting the panorama in the windshield except for the one constant: the endless sky that blankets the landscape, where cloud after cloud fades into the distance. In a storm, the smectitic soil soaks up the rain. That’s expansive clay. It pulls on the wheels of my car. The road, however, is rarely impassable this time of year. The Bureau of Land Management almost never closes the quarry unannounced. At the quarry, ruby red Claretcup cactus bloom in the desert soil alongside the familiar Castilleja, or Indian paintbrush. It is worth a moment to stand and scan the horizon. I do a 360.

"The quarry asks its visitors to help solve the mystery. What brought so many dinosaurs to perish in this place?"

Photo: Mark Osler

Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry

Photo: Mark Osler

Footprint of a giant left in the San Rafael Swell.

Photo: Dean Krakel

Experience the densest collection of Jurassic-era dinosaur fossils ever discovered.

Photo: Dean Krakel

This is a colorful, wondrous place. Those are quarry steward Jessica Uglesich’s words. But it is also a rugged and less familiar part of the Colorado Plateau compared to its more celebrated peers in Southern Utah.

The quarry asks its visitors to help solve the mystery. What brought so many dinosaurs to perish in this place? The landscape was very different back then, but I contemplate the neat parallel to today. Who comes here, and why? When I arrive, Jessica is running through the hypotheses with Richard and Deane Bunce of Berkeley, California. I ask what brought them to Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry.

“When we go to different areas we try to find out as much as we can about the history, whether it’s a city or out in the wild where we do a lot of backpacking,” says Deane. “Whatever is left that manifests some of the culture that used to be here.”

Richard adds, “We’ve traveled around the world for as long as 15 months at a time. Southern Utah is one of the few places in the world that we keep coming back to.”

Minutes later, Jim and Marion Cheatle of Nairobi, Kenya, arrive and Jessica engages Marion in the quarry’s scenarios before the couple set out to explore the museum, then continue to the Butler Buildings that protect the deposit, and the site’s hiking trails.

It appears that ranchers discovered the site, but record keepers from that era’s paleontology didn’t capture the name. Clearly they were too excited to dig into the limestone, which seemed to have a tremendous number of fossils. It would turn out to be the world’s densest concentration of dinosaur bones. More than 12,000, so far.

Michael Leschin is a geologist and paleontologist for the BLM Price Field Office.

“We’re here to point out how amazing this deposit is. And the way we do that is presenting evidence. Nobody has to believe us, but science is a marvelous way to think. There are so many different avenues in science that all come to the same conclusions,” says Michael.

That is not to say that stories don’t evolve. Cleveland-Lloyd’s own story has shifted from possible predator trap to swamp to some kind of toxicity. It’s best to ask the quarry stewards about it.

“Paleontology changes by the week,” says Jessica. Her co-steward Nicole Stouffer nods in agreement. Books and academic papers discussing the latest in the field surround them.

Michael comments, “Cleveland-Lloyd really reflects the evolution of paleontology as a science, from when simply coming back with good dinosaur bones was good science to today when we’re photogrammetrically recording the dig and running geochemistry of the site as we do.”

In other words, researchers deploy modern technology to get a much more complete picture of the paleoenvironment. It’s no longer just finding and taking objects. It’s a deep understanding of the nature of the objects. The approach to paleontology echoes the Bunces’ — and my own — approach to travel. It gives me so much to think about when I set out on a hiking adventure.

The Swell Season

The Wedge Overlook of the Little Grand Canyon kind of sneaks up on me. We drive east from Huntington until the well-marked turn to The Wedge. From there, it’s a winding six miles to the rim. At times, I get the sensation when looking out across the rolling plain of juniper, pine and desert that there’s something out there. Suddenly, we’re at the rim, with a few big rocks and a view 1,200 feet down to the San Rafael River.

We’ve followed Lamar Guymon of San Rafael Country Adventures out to the rim, a place he’s been many, many times and holds sacred. (See “In a Sacred Place”) There’s no preparing for the view, but its effect is immediate. Lamar sums it up:

“There’s nothing more peaceful than when you’re mad at the world, and usually everyone that lives in it, and you come out and sit on one of these points and just look and think and meditate and get all that hate out of your system. That poison. Then you can go back to life again.”

There’s a wind off the canyon that carries a perceptible chill. It had been our intention to camp on the rim, but we decide it will be a little warmer down in Buckhorn Draw, more than 1,000 feet lower in elevation. The next day, we’ll work our way back up through the pictographs and other interpretive sites.

We opt for a signed, but primitive, site tucked into the rocks off the side of the road. It is nearing sunset so I get my tent set up then go about building a fire. The skies are clearing and there will be stars tonight. I am exhausted from the day exploring but know I’ll wake up in the pure darkness of the draw.

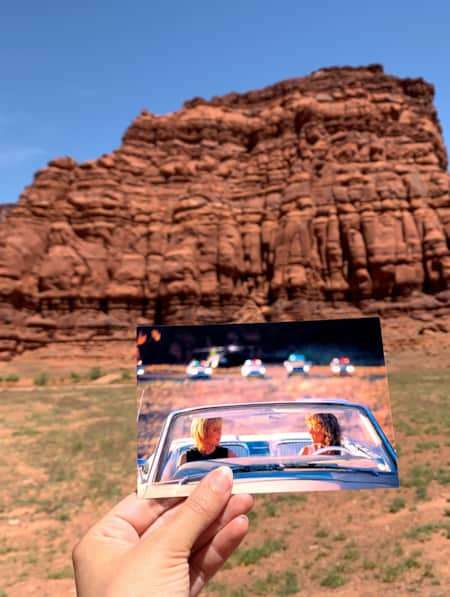

Here’s the thing about the San Rafael Swell: Like so many travelers, I had driven down U.S. 6 toward Moab not knowing what was out here. I probably saw the San Rafael Reef, the easternmost edge of the San Rafael Swell, a half-dozen times.

"All of what you’re looking at right there will more or less be the same a thousand years from now as it is right now."

Photo: Dean Krakel

Nine Mile Canyon

Photo: Dean Krakel

Photo: Dean Krakel

It’s not exactly a secret. Goblin Valley State Park is a national treasure and a well-known piece of the Swell’s landscape. The visitor log at the Buckhorn Wash Pictograph Panel contains pages and pages of names just from the first few months of the year. But there is a lot that people don’t see. Even on this trip Lamar sees an arch up on a ridge he’d never seen before because he was taking his time, and stopped in the exact right place.

I would call Buckhorn Draw and The Wedge “An Introduction to the San Rafael Swell.” I think about what little I’ve seen as I hike a few miles around the Good Water Rim. The trail is lovingly blazed around the complex canyon. I imagine it from space looking like those classic fractals. I’m not sure I had any hatred in me when I arrived, but I sure am at peace right now.

The 46 Miles of Nine Mile Canyon

The Book Cliffs are a massive formation. The shale and sandstone escarpment stretches 200 miles from Price Canyon into neighboring Colorado. It forms a layer cake backdrop to the corridor from Helper, Price and Wellington and on down to Green River. Nine Mile Canyon is a natural conduit through the cliffs, and is famous for its well-preserved and abundant collection of prehistoric petroglyphs, some of the finest examples in the United States. (Read: "A Rural Community Leading the Way in Stewardship and Preservation")

Nine Mile Canyon Road, your guide for this journey, is one beautiful road. Truly, the asphalt itself is in near-pristine condition, having only been paved in 2014. A convergence of industry and conservation finally brought about the improvement — and it is an improvement. Years of increased use saw dust and dust suppressants kicked up by traffic, blanketing the sensitive petroglyphs.

Nine Mile Ranch’s 77-year-old Ben Mead agrees.

“Everyone said you get that road paved and the traffic will kill you. But it really hasn’t been much difference. It’s so much quieter now and with none of the dust and rattle you don’t even notice the traffic.”

Mead purchased the ranch after working 22 years down in the valley for the Plateau Mining Company. Today, the rustic ranch offers some of the area’s only lodging to travelers passing through. At the time I catch up with him, he’s methodically building a stone chimney addition to their largest guest cabin. The cabin is one of three homesteads relocated from elsewhere in Nine Mile Canyon and carefully restored on-site. He has a kind, weathered face beneath his Stetson. I half-expect him to encourage me to figure out the one thing that brings me meaning in life. To find his wife, Myrna, Ben hops on a mountain bike and rides up the hill to where they’re clearing a field for a parking area in anticipation of their 20th anniversary celebration.

We drop off our gear and head down canyon to see a small handful of the more than 1,000 catalogued sites.

In the canyon, low-hanging clouds dance across the fir-lined hillside like smoke signals or a campfire. The rain activated the desert sage, filling the site with fresh, sweet aromatherapy. A few paces west, pinyon seeds litter the canyon floor from a stand of pines. When I walk, I stir up cottontail rabbits and grouse. Ravens reflect their squawks high up on the cliffside of the narrowing canyon, which is streaked with mineral deposits and dotted with dark green junipers.

When I approach the Big Buffalo Panel about 45 miles up the canyon, grazing cows call loudly to each other as they convene in a nearby field. Their urgent mooing haunts the canyon as it bounces off the walls and fills the space like an amphitheater.

Around the corner, there is an interpretive sign at the Great Hunt Panel suggesting the panel represents an actual event. It raises questions. Was the hunt great? If so, to whom is the artist proclaiming its greatness? How long did it take to record this event? To carefully peck away at the soft, yet durable wall?

There’s a palpable human texture to Nine Mile Canyon. Humans have layered their existence on the rock walls and canyon floors. Waves of the so-called Fremont Culture left their messages in stone and disappeared or were absorbed into other indigenous groups about 1,000 years ago. Maybe a people before them shook their heads at this new form of art. Early homesteaders settled and built lives. Here, the abandoned stone home where Ben Mead’s parents lived, expertly cobbled together. There, the remains of the ghost town Harper mark a once-thriving stagecoach stopover. Further along, only the stone chimney of a now vanished house remains. What family gathered at its hearth? I naively think of these as long-ago broken dreams. Maybe they’re just forgotten dreams, the way the memory slowly slips away, the longer you’ve been awake. Today, energy development and grazing are prominent. So many different lives and worldviews have passed through here. Meanwhile, Nine Mile Creek continues its patient erosion.

What's Nearby

-

Base Camp Green River

It’s time to leave the city and the suburbs behind and drive through the mountains and canyons into the Utah desert. True, Green River is barely an hour away from Arches and Canyonlands national parks, so those are options to extend your 3-day trip. But for this itinerary, we’re focusing on the local secrets: the hidden labyrinth of slot canyons and whimsical hoodoos of the San Rafael Swell and the dining and heritage that are part of the unique fabric of Green River.

-

Capitol Reef Petroglyphs

Capitol Reef is home to towering sandstone structures and impressive canyons, but it also holds many ancient petroglyphs, which are engraved etchings into rock walls.

-

Millsite State Park

MIllsite State Park in Central Utah is an outdoor paradise with boating, fishing, biking, hiking, camping and more. Plan your visit today!

-

San Rafael Swell

San Rafael hikes and bike rides offer unique terrain and jaw-dropping scenery. Learn about the area’s trails and start planning your trip!