Utah Female Artists Explore the Sublime Through Art

At the intersections of landscape, domestic life and religion, female artists have created a renaissance in Utah.

Utah reminds me I am small, and that the landscape is ancient, wise and encompasses both time and mystery. Once, on a drive to San Francisco, I came to the Bonneville Salt Flats at dawn and my boyfriend and I stepped into the shallow layer of water resting on top of the cracked and endless white salt. Something in me shifted, some belief in the surreal awoke.

The varying landscape of Utah is so much larger than I will ever understand. That seems to be a common preoccupation of a generation of female artists who have grown up and around Utah landscapes like wildflowers, each creating according to her own experience.

Many Utah artists are inspired by a unique intersection — a physical landscape that begs to address the sublime in contrast to a cultural landscape that often supports or grapples with a ubiquitous belief in Christian divinity. The field is ripe with tension and awe, and throughout the state female artists are facing what it is to create amongst such spiritually relevant questions and so much natural beauty. Here are excerpts from conversations with 14 artists, whose work — across a variety of mediums — represent a female renaissance in Utah-anchored art.

"The field is ripe with tension and awe, and throughout the state female artists are facing what it is to create amongst such spiritually relevant questions and so much natural beauty."

Emily Fox King.

Emily Fox King and kiddos.

Artist Emily Fox King

The Landscape of the Domestic In Utah Art

In the early 19th century, Minerva Teichert a well-known artist of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints religion, was known to take a bouquet of flowers from a funeral and return them in the form of a painting for the grieving family the following day. Her life was made up of both the landscape of the domestic, and a living room full of paintings that she used as barter to send her children and the children in the neighborhood to study at Brigham Young University.

As a hopeful, burgeoning artist in college, I knew the work of Teichert well, and my idea of her encompassed everything I aimed to be at the time: a successful artist with a handful of children running through the studio.

Many of Utah’s female-identifying artists are raising children while simultaneously forging a career. This can yield a vibrant cache of creative work both within those bounds and work that pushes against them. This intersection of women entrenched in the domestic while pushing forward in artistic careers makes fascinating and relevant art.

There’s a strong sense of community among Utah’s female artists, in a scene marked by collaboration, rather than competition. I believe this is created by a confluence of both the problems and the beauty that come with creating in a setting where a Christian religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is a part of so many current or past lives.

Utah painter Emily Fox King creates within this domestic structure, and also pushes against expectations and assumptions. “I hope my flower paintings convey beauty and chaos, with the richly-layered paint, fiercely and aggressively applied,” the artist said in an interview with Segullah, a female-run online Latter-day Saint literary journal, explaining that viewers often consider her paintings to be “happy.” “I want to reply, ‘No they’re not, can’t you see the RAGE?’ But that’s my point. I think life, motherhood, womanhood, is a mixed bag of beauty, chaos, uncertainty, anger and resignation, all in one.”

Elizabeth Sanchez, a Mexican-born, Latter-day Saint who paints quirky depictions of the domestic mingled with symbols and images of her heritage, underscores the support she has found for her work. “To all the artist moms trying to find balance in motherhood and being creative — there isn’t such a thing,” she says. “However, focusing your attention between the two doesn’t make you less artist or less mother.”

Susan Krueger Barber began her art career after college making paintings during her young children’s naptime, before eventually turning her art-making practice into full-fledged local activism. In 2015, she literally buried herself in dirt and emerged with the alter ego “Art Grrrl,” oftentimes dressed in a homemade superhero costume. A recent project consists of placing hundreds of figures around her neighborhood. These figures have heads encased in a mold of jello as commentary on her religious roots (in cultural lore, Latter-day Saints love Jello), and the idea that viewers perceive morality, politics, spirituality and life in general through their own particular lens of experience. “The environments and events I generate borrow meaning from the complex and sometimes conflicting origin stories of my respective lineages, namely: DIY, Queer, Feminist and Mormon,” she says in regards to herself as an artist.

Representations of God, and in more recent history, the addition of a female God, play a part in the art created in Utah. Many artists create work directly in relation to Latter-day Saint doctrines. This body of work is evolving and in many ways being led by women who insist on taking charge of the way they understand and perceive their spiritual experience. A few years ago the work of Caitlin Connolly could have been seen as subversive, or on the edge of the Latter-day Saint canon, but in recent years, the institution itself has embraced representations of a Heavenly Mother. Connolly’s work also depicts struggles with infertility, and her own evolution to a mother of twins, as she paints female figures as holy and powerful, often in communion with other women.

In her work, Paige Crosland Anderson seems nestled in the intellectual space of the domestic. “Pioneer quilt patterns are symbols of my cultural heritage,” says Anderson. “Not only am I the descendant of Mormon pioneers who crossed the plains but also my grandmother Donna was an expert quilter.” That adds context to viewers who see the layered and seemingly endless patterns of her paintings. “I paint the same pattern several times in different colors until there are an indiscernible number of underlayers,” Anderson says of her process. The paintings feel indicative of what a traditional spiritual life can look like, repetitious, even dull from the outset, but rich with texture, color and surprise the longer viewers look at it.

"A recent project consists of hundreds of figures whose heads are encased in a mold of jello as a commentary on her religious roots, and the idea that viewers perceive morality, politics, spirituality and life in general through their own particular lens of experience."

A piece by Susan Krueger Barber titled, "Latinx Woman Purse Jell-O Head."

I'm Listening For The Language of Women

From fighting for voting rights to experiencing the wild lands today, women are exploring and shaping Utah’s past and present.

On the Land We Stand

Salt Lake City-based artist and University of Utah associate professor Beth Krensky creates solo performance work set on the Bonneville Salt Flats. “I think it is important to understand on what land you stand and what has transpired on the ground under your feet long before you arrived,” she says. “There is beauty, suffering and many layers of history from different peoples who have imprinted the land.”

In “Make Me a Sanctuary,” Krensky walks across the salt flats in a white linen dress embroidered with biblical text referencing the idea of a tabernacle. As she walks, she holds two olive wood poles connected to a personal “tent” or sanctuary that is created as she walks. This communing with nature, rather than trying to harness or change it, feels representative of the casting out toward the sublime that many Utah artists seem to have in common.

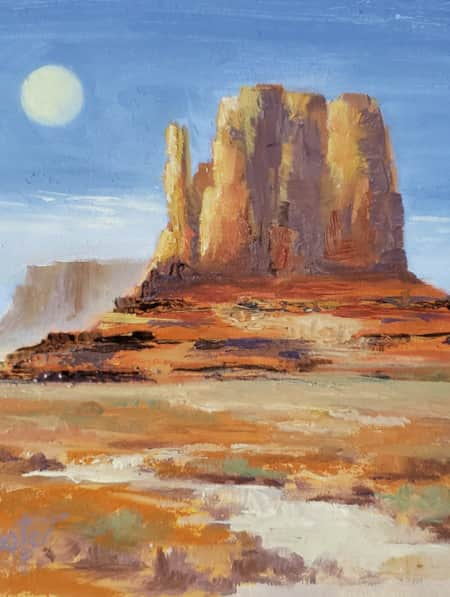

Anne Kaferle based in the up-and-coming art hub Helper, creates dreamlike and surreal landscapes. For the past seven years, she’s taken daily hikes, observing changes in light, cyclical changes, weather and subtle color variations with a painter’s eye. “The balance of color, value and line in the desert landscape has a serene power, and this is what I’m trying to communicate in my work,” Kaferle says. (Read: Turning Carbon into Culture)

On the other side of the Manti La Sal Mountain range, another desert oasis of artists live and work in a town pioneers once built: Spring City. The town’s artists include the well-known “Matriarch of the Arts,” Ella Peacock, who painted plein air landscapes in natural tones which she set in her hand-carved frames. Contemporary and successful artists such as Lee Udall Bennion and Kathleen Peterson thrive in making tribute to the land by living on and with it, taking in colors, scenery and history as part of their daily and artistic practice. “Where I live and how I live has everything to do with my art work,” Bennion says. “I have never painted too far from home, meaning I paint people, animals, places and objects that have meaning to me and that I am very familiar with. I think finding a place on earth where you feel at home and connected is extremely important.” (Read: Gleaning a Small Town's Harvest)

Back in Salt Lake City, Claire Taylor, another artist harboring an intense reverence for the natural world, creates rich, visceral paintings depicting Utah’s animals in both rural and urban landscapes.Taylor’s work harmonizes with animals and nature in all the places they cross paths with her — urban neighborhoods, cemeteries, parks and local trails, as well as the more untouched spaces in the state. This year she is an artist-in-residence at the Natural History Museum of Utah, where she is compiling a “mind map” painting that evolves, cumulates and flows as she paints and draws Utah’s animals. Children watch as she paints at the museum, offering their own versions of nature as they paint and draw beside her. “The landscapes here in Utah are where I find spiritual food,” Taylor says. “I am able to wrestle with existential spiritual questions in nature.”

Artists who work in all sorts of mediums are doing the work of interpreting the land into art. Lenka Konopasek, who emigrated to Utah from Czechoslovakia, has created a handful of public sculptures installed around Salt Lake City. Her work can be seen at the Old Greek Town Trax station, the downtown Public Health Clinic, 337 Pocket Park, the Art Shop Project in The Gateway, and the Mclelland Trail. “A lot of times I use shapes and colors derived from natural formations and surrounding landscape in an abstract way,” she says. “It is almost impossible for me not to be affected by my surroundings and it reflects in the art work.”

The People Who Stood on this Land Before Us

While Utah is experiencing a renaissance of female-created art, the state’s dramatic landscape has been inspirational for generations. Before Latter-day Saint pioneers and many others settled in Utah, the land was home to the Shoshone and Bannock tribes in the north, Ute and Goshute tribes in the central section, and the Southern Paiute and Navajo tribes in the south.

Kwani Povi Winder, who comes from the Santa Clara Pueblo tribe in New Mexico, has made a home in Ogden, where she engages with her Native heritage and contemporary culture through her art. Although her initial work featured Latter-day Saint imagery, in the past couple of years her paintings have evolved to be primarily about her Native American heritage. She says there are few classically trained oil painters who are American Indians, and she aspires to represent her people through her work. Her paintings are striking, as they seem to embody a tribute and search for the sublime through depicting tradition and ritual. She seems to be reaching both into cultural memory while also giving image to the present, and in doing so, honoring a future where American Indian culture is honored. “I’d like to think that my paintings create a bridge from the present to connect to our ancestors,” she says, adding that she likes to focus on capturing youth in traditional dress. “They represent that Native Americans are still alive, thriving and continuing to pass along their culture to future generations.”

Where the Cultural and Physical Landscapes Intersect

There’s another tension that courses through Utah-based artwork: the complexities of transitioning away from the predominant faith. Leaving a religion requires a re-imagining of the sublime, and suggests the creative work of entering different waters.

Miriam Tribe is someone who has created into the opening of a new spiritual life. “My personal faith transition required a lot of rebuilding and reinvention,” she says of her artistic process. “I discovered my artist-self at the very same time I was reimagining my own spirituality, and in retrospect I can see how closely related the two evolutions were for me.” Her work is a clear extension of her physical body, both in creation and final product. To watch her create drawings is almost a mystical experience, as her hand rarely leaves the paper and she often draws with both hands simultaneously. It seems as if she is casting a spell with her contour lines and subsequent color. “I circle around a lot of questions about identity and relationships,” she says. “I use lines like choreography, and color like ritual or war paint — defining the primal inner state, the true intention,” she says.

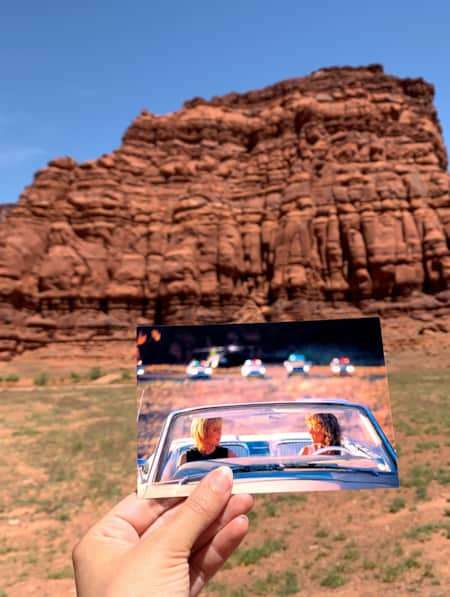

Laura Hendricks re-imagines landscapes by combining photos into collages that feel at once familiar and disorienting. “I used to feel conflicted about changing images of landscapes since the scenes are what they are and I love them as they are,” she says. “Later, I started removing the belief systems and lifestyle elements of my life that didn’t, and had never really did, work for me, and adding ones that did.” The post-religious space can be a rich, sometimes painful, often liberating journey that can make for great art, and adds to the colorful tapestry Utah artists are weaving.

Annie Kershisnik Blake generates series of paintings on a single theme or word for each collection. Her art cultivates an evolving relationship with the natural and spiritual world beyond the Latter-day Saint faith she grew up in. “Female art in Utah is a specific feminist statement,” she says. “It’s about claiming space, building confidence and asking to be included in spaces that aren’t thinking about you.” Utah has its own versions of patriarchy that artists push against, while still connecting to the overarching issues of patriarchy that the art world at large is working through. This strong sense of building each other up, recommending, collaborating, marketing and creating micro-economies with their artwork happens across cultural, religious and artistic differences.

"The land here asks questions of divinity, of the sacred, of what it is to reckon with small lives against the backdrop of the giant gatekeepers called mountains, of the rolling red desert, of the living expanse of the salt flats."

The natural world is the impetus for many of the artists forged in Utah. The land here asks questions of divinity, of the sacred, of what it is to reckon with small lives against the backdrop of the giant gatekeepers called mountains, of the rolling red desert, of the living expanse of the salt flats. Artists and viewers reckon with the fact that at one point, nearly the entire region was covered by an ancient lake, and its shoreline is still marked on the mountains. Oceanic fossils litter the tops of almost every mountain along the Wasatch Front, making literal the Bible prophecy from Isaiah 40:4: “Every valley shall be raised up, every mountain and hill made low.” Artists create in the wake of this history that we are just a tiny blip in.

It seems the collision point of such a wide variety of work is in the dogged search for the sublime. Artists in Utah, while creating vastly different work, are crossing each other in all sorts of beautiful ways. This attempt to capture and understand the sublime comes from engaging directly with the distinct landscapes and wildlife that surround each artist. These artists have to reckon with the empty expanse of what nature and religion often are, which is imagination. None of these landscapes offer an emptiness of possibility; they all require a shove against the parameters, an attempt to capture what is too big to capture, just to see what might happen. (Read: Where to See Women's Art in Utah).