A Matter of Geological Consent

A billion years of geological history surrounds Salt Lake City, where a modern landscape reflects ancient constraints.

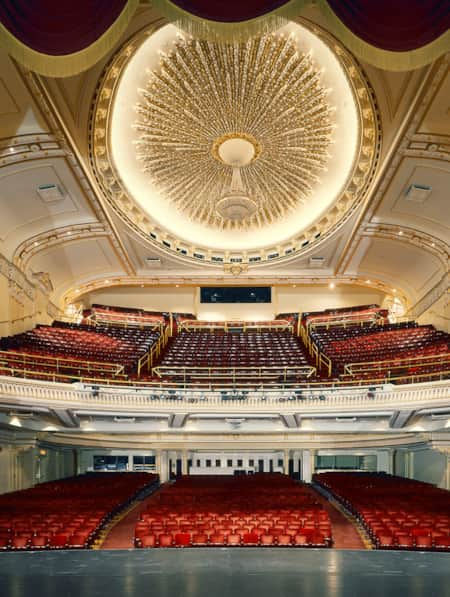

Spread out in a variegated muted velvet quilt of greys and greens, the sparkling lights of Salt Lake City’s distinctive gridded streetscape stitches together the valley’s level floor in even blocks. The abrupt, wavy border of this patchwork is defined by an uplifted fringe of scattered illumination from homes perched along the mountain foothills. With the sun just cresting the Wasatch Mountains, the first light of day reflects gold-hued red on hard angles of downtown’s tallest buildings in the valley below. It glints off of the distant Great Salt Lake with the flat shimmer of beaten silver, and the rounded dome of the state capitol building glows like a ripe halved peach.

"In the greater Salt Lake Valley, geologic time is an in-your-face and immediately relatable record of rocky millennia past and uncertain seismic realities present."

On this crisp early fall morning hike along the Bonneville Shoreline Trail just above the University of Utah’s sprawling Research Park, I pause to catch my breath after a steady ascent from the trailhead parking lot hits me with the reminder that the modern city in which I live is ever filled with surprises. I’ve hiked this trail hundreds of times with my two Labradors trotting ahead on their own sniffing missions, yet the experience is always subject to change. The weather, run-ins with local wildlife, or on this day, smoke particles from nearby forest fires add atmospheric drama of deep pink and orange as the sun continues to rise.

And from this spot just above the linear grace of the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU) — copper-cladded with siding mined from the you-can-see-it-from-space Rio Tinto Bingham Canyon Mine, a massive swath dug out of the flank of the Oquirrh Mountains looming along the western edge of the Salt Lake Valley — I’m hit with a visceral reminder of how very different the same view might have looked to the region’s earliest humans at their arrival sometime between 13,000-14,500 years ago. When where I now stand was just above the shoreline of a massive, inland, freshwater lake stretching as far as the eye could see, hemmed in by the steep jut of glacier-capped mountains. Dinosaurs trod here in Early Jurassic time 201.3 million years ago. And even farther back to the Paleozoic Era, I’d be standing on the Sahara-like sand dunes of North America’s west coast 300 million years prior. It’s a spectacular landscape containing the history of multitudes, writ large on hillsides and discernable immediately. I’m reminded of the words of Pulitzer prize-winning chronicler of landscapes, John McPhee, when I’m explaining the ‘why bother’ imperative of geology: “If by some fiat I had to restrict all this writing to one sentence, this is the one I would choose: The summit of Mt. Everest is marine limestone.” In the greater Salt Lake Valley, geologic time is an in-your-face and immediately relatable record of rocky millennia past and uncertain seismic realities present.

The Ancient Context of Constraint

"A map, it is said, organizes wonder,” wrote writer and Utah-landscape-enthusiast Ellen Meloy in "The Last Cheater's Waltz: Beauty and Violence in the Desert Southwest." For me, a geological map is the best sort of organizational prompt for exploring the Wasatch Front, along with my trusty dog-eared copy of "Roadside Geology of Utah" by Halka Chronic. (Pro-tip: Most U.S.-Geological Survey maps are available online at no charge, but for old-school paper map collectors/hoarders like me, a stop at Salt Lake City’s the Utah Department of Natural Resources Book Store is a must-do). But it doesn’t take an intermediary geological interpretation to get to the basics of how surprising the Salt Lake valley’s environment is.

You just need to look up, and look around.

During a recent visit to the NHMU, I talked with Chief Curator Dr. Randall Irmis about the unique geographical boundaries that have determined our modern urban landscape. As a geoscientist by way of being a paleontologist, Irmis extols Utah’s landscape as a phenomenal incubator for science education. “Geology is an intuitive natural science; with our naked eye we can see how it works,” he says of the world all around us. “We can see ripple marks in a modern streambed, then look up and see a 200 million-year-old layer with ripple patterns formed the same way.”

Irmis points to how the retreating and advancing shoreline of ancient Lake Bonneville over tens of thousands of years shaped our current environment. “Although it was freshwater and had different levels at different times, Lake Bonneville shaped the geology and geography of the Salt Lake Valley and Wasatch Front.” Irmis points to the city view visible from the central gathering space of the museum, called The Canyon in a node to Utah's famed formations. "It's the reason why we have distinct benches along the valley, and it determines the sediment our city is built on,” with fine grain mud deposits underlying the streets of downtown, and relatively recent (in geologic time) soft sediments framing much of the valley floor. As a result, says Irmis, “Ice Age fossils are found in seemingly very unlikely places in Utah.”

He shares the example of one of the earliest fossils added to the museum’s collection: a late Pleistocene musk ox skull found during construction of a cellar in 1871, near the intersection of State Street and South Temple in downtown Salt Lake City. Since that early discovery, scientists have identified other now-extinct Pleistocene megafauna like mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, camels and saber-toothed cats. As the climate changed, Lake Bonneville shrank (remnants of this are the modern-day Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake) and high alpine glaciers disappeared. The animal record of this dynamic shift lives on today in Utah’s wildlife descendants like big-horn sheep and bison.

The museum spans five floors, exploring the wonders of life, earth and culture.

The Natural History Museum of Utah tucked along the foothills of the Wasatch Mountains.

Informed by the Basin and Range

Going back even further in geologic time, the creation of the Basin and Range Province — stretching from Sonora, Mexico, in the south up to southeast Oregon, and starting west from eastern California to the east in central Utah — informs the series of mountain ranges and vast high desert expanses of the modern Intermountain West experience. Pioneering 19th-century geologist Clarence Dutton described the region’s unique vertical tectonics as, “many short, abrupt ranges looking upon the map like an army of caterpillars crawling northward,” which then divide into two columns: Great Basin’s ranges of Utah to the northwest and the Rockies north-northeast. I think of these tectonics like stretch marks, with the birth of mountains and fracture of faults adding texture as the belly of the region deflates and expands over time.

At the end of the Oligocene Epoch some 25 million years ago, a rift between two oceanic crustal plates along the western edge of North America subducted (collided and were forced under) beneath the western edge of North America. This formed what is now the San Andreas fault system. The resulting forces on the continental plate stretched and extended between two fractures, with eastern limits at the Wasatch Fault along Salt Lake City, and to the west, California’s San Andreas Fault. “Rocks near the Earth’s surface don’t pull apart like taffy,” says Irmis of the pull-stretch-give formation of this distinct topography, “They break, and some chunks go up, some down.” The blocks that go up? Those are mountains. Basins are (you guessed it) where gravity takes over and the blocks subside.

And it’s still going on, a fact made very real to Utahns in March after the 5.7 magnitude earthquake. The Wasatch Front’s continued seismic activity has informed how buildings have been designed since the 1970s, including earthquake-stabilizing upgrades to landmarks like the Utah State Capitol and buildings around Temple Square. Visitors to the NHMU can get a first-hand glimpse of how scientists and engineers work together to make buildings safe along seismic zones; the LEED-certified museum is anchored with a complex lagging support system anchored with columns drilled 80-feet deep into bedrock, and rock excavated from this process forms the distinctive rock gabion walls of the museum terrace.

Says Irmis of our unique urban setting, “The Wasatch Front is pretty amazing,” with a complex and rich geologic history. You’ll find 1.7 billion-year-old gneiss formations at Antelope Island in the Great Salt Lake. In Little Cottonwood Canyon, there are 1 billion-year-old remains of ancient marine environments, climbers cling to quartz monzonite and granite surfaces 31 to 26 million years old, and the U-shape of the canyon tells the erosion story of the 12-mile-long glacier that once stretched from Albion Basin (at Alta Ski Resort) down to ancient Lake Bonneville beginning about 30,000 years ago. All of this is overlaid with more recent Ice Age sediments just a few thousand years old. “You can go 30 minutes in any direction and you can learn most of the geologic history of the Earth right here,” says Irmis of the Salt Lake Valley.

"The Wasatch Front’s continued seismic activity has informed how buildings have been designed since the 1970s, including earthquake-stabilizing upgrades to landmarks like the Utah State Capitol and buildings around Temple Square."

Today’s Urban Corridor

Although living in the foothills of the Wasatch doesn’t bring me in contact with mastodons and saber-tooth cats (thank goodness), the geography and soils of our narrow valley influence our modern interaction with wildlife on an almost-daily basis. This long, relatively narrow urban area is hemmed on one side by the abrupt rise of the Wasatch Mountains, and on the other by high, scrubby deserts surrounding Great Salt Lake. Our rather unique and immediate access to the outdoors is a huge draw for visitors, with snow sports, hiking and mountain biking just minutes from the city center. With that comes a complex and dynamic interface between humans and the region’s wild inhabitants, with moose, mule deer, elk, wild turkey, bobcats, coyotes and other wildlife competing for cover and resources.

The food resources indigenous to this region determined where people have settled and thrived since the earliest humans arrived in the area 13,000 years ago through to the current day. At the tail end of ancient Lake Bonneville’s extensive range, archaeologists have recorded that the landscape was abundant with wildlife and huge glacial lakes teemed with fish. Stories of this abundance chronicled by Ute, Paiute, Goshute and Navajo people continue through generations present today. As people domesticated animals and cultivated food production in the Salt Lake Valley, geology determined the nutritive value of soils. Whether rocks are porous or non-porous determined access to the water table for irrigation and drinking. And transcontinental bird migration routes reflect the basic needs of food, water and cover found for tens of thousands of years along this intermountain flyway, a boon to international birders who flock to the Salt Lake Valley annually to check off rare species sightings on their life lists.

As 19th-century populations grew exponentially throughout the west, the variability of the Basin and Range landscape shaped where transportation networks followed natural pathways of resistance or (literally) blew through them, as in the case of wagon trails, Pony Express routes, and most dramatically, the Transcontinental Railroad. Rare natural resources extracted from Utah’s mountains informed where mining communities sprung up in Park City, Bingham, Alta and all along the Wasatch Front. And many of the Salt Lake Valley’s earliest extant buildings are made with stone quarried nearby. Red sandstone sourced near today’s Red Butte Garden was used to build historic Council Hall (home to the Utah Office of Tourism offices), and the gray granite-like stone (quartz monzonite) found in Salt Lake’s Temple Square was quarried beginning in the 1850s at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

Culture Inspired by the Geology of Constraint

In addition to the many opportunities for roadside geologic interpretation scattered throughout the surrounding canyons and salt flats, Utah’s unique geographical conditions have inspired creatives on scales large and small, in instructional ways like the “Past Worlds” exhibit hall at the NHMU. Or, in more subconscious fashion, such as the way that Utahns almost by cultural default describe location in relation to the mountain ranges surrounding the city: the “Wasatch Front” and “Wasatch Back” on either side of the mountain’s spine, “Point of the Mountain” describing a sharp jog in the range near Alpine, and the “East Bench” following the ancient Lake Bonneville shoreline.

Famed Spiral Jetty artist Robert Smithson captured this tension of the abrupt jolt from urban convenience to the harsh beauty of Great Salt Lake’s shore when he described going to the remote site was an intentional act of observance essential to the experience of the work itself. “The route to the site is very indeterminate," Smithson wrote. "It’s important because it’s an abyss between the abstraction and the site, a kind of oblivion.”

Philosopher and historian Will Durant famously wrote, “Civilization exists by geological consent, subject to change without notice.” This geological imperative has also influenced the creative outlets by which people have expressed their surprise, wonder and excitement for the unique perspective determined by the Salt Lake Valley’s narrow corridor. It’s equal parts jarring and exhilarating to experience within one day the juxtaposition of snow-capped mountain peaks and bone-dry scorching desert, with water too salty to drink.

A Quick Guide to the Bonneville Salt Flats

Here's everything you need to know to visit and plan for Salt Lake City's nearby Bonneville Salt Flats.

Where to Go

Bonneville Salt Flats

Northwestern Utah

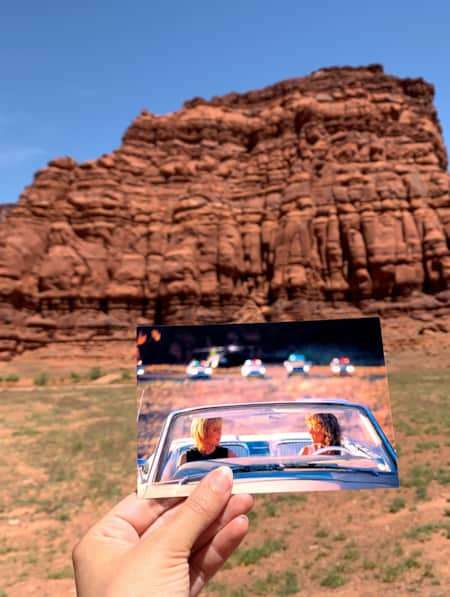

Movies have been filmed at this otherworldly landscape, where the curvature of the earth is visible with the naked eye. Weather permitting each September, it’s the site of record-breaking land speed records set during the “World of Speed” trials.

Metaphor: The Tree of Utah

25 miles east of Wendover

It’s everyone’s double-take “what the heck?!” driving on I-80 on the Salt Flats. Iranian-born Swedish artist Karl Momen created the 87-foot-tall concrete sculpture in 1986 as a nod to the paradoxical fragility and fierce conditions of the landscape.

Spiral Jetty

Northeastern shore, Great Salt Lake

Sculptor Robert Smithson’s famed 1970 earthwork is one of the most well-known installations of land art in the United States (Read: At 50, the Spiral Jetty, Utah’s Most Iconic Land Art Sculpture, Keeps Drawing a Crowd). No two Spiral Jetty trips are ever the same, with the lake’s unique biochemical color changes and water depth influencing the visitor experience (Administered by Dia Art Foundation, see directions and visitor tips). Visitors should be mindful that low water levels at the Great Salt Lake have increased the natural presence of tar around the Spiral Jetty shoreline. Watch your step and keep dogs on leash.

Golden Spike National Historic Site

Corinne

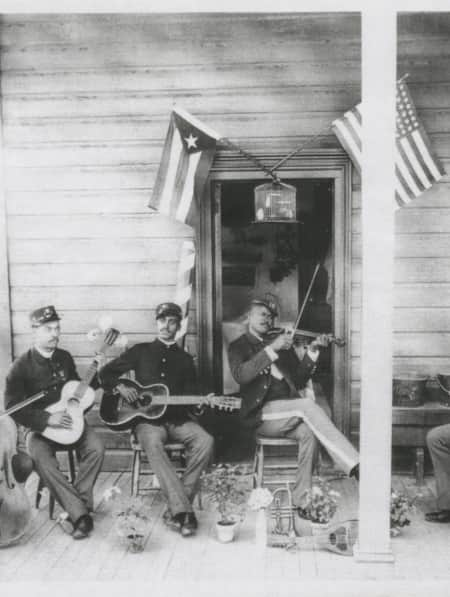

Revisit the historic pivotal event bringing transportation, technology and resources networks across the country in 1869. Walk or drive on parts of the abandoned railroad grade, and get up close-and-personal with replica Victorian-Era locomotives. (Watch: The Golden Spike Unites a Nation)

Rio Tinto Bingham Canyon Mine Tour

Herriman

This tour starts at the Lark visitor parking area. After check-in, visitors are shuttled up to the Bingham Canyon Mine overlook and can see the massive mining operation, which is one of the largest in the world. Open April – October, weather permitting (Reservations highly recommended; 8:30am – 3:00pm 7 days a week).

Pony Express National Historic Trail

West Desert

Follow in the hoofprints of the West’s famed horse relay news delivery system along this remote and unpaved roadway. Plan ahead with a 4WD high-clearance vehicle recommended and bring in all your own food, water, backup gas and other supplies. Recommended stops along the trail are Simpson Springs and Fish Springs National Wildlife Refuge.

Antelope Island State Park

Accessed from Syracuse

Here you’ll find some of the oldest rocks in Utah (1.7 billion-year-old gneiss) to more recent Lake Bonneville sediments. Check out the unique oolitic sand beaches created when sand-size particles of calcium carbonate form in egg-shaped ooids from the agitation of wind and water rolling the grains around.

Eccles Wildlife Education Center

Farmington Bay

The Great Salt Lake's environment is crucial to the survival of hundreds of bird species. Visit this new education center to get oriented to this rare ecosystem.

Bonneville Shoreline Trail and the Natural History Museum of Utah

Salt Lake City

Visit the “Past Worlds” exhibit at the NHMU to get oriented to the Wasatch Front’s unique geologic past, then explore the shoreline of ancient Lake Bonneville on foot from the trailhead at the museum.

Little Cottonwood Canyon

Salt Lake City, Alta

Hike or mountain bike the Temple Quarry Trail to see where Temple Square’s building materials originated. Check out the Salt Lake County geologic view park near the intersection of Little Cottonwood Road and Wasatch Boulevard. The remnants of Alta’s once-thriving mining district can be seen while hiking or skiing at the resort at the top of the canyon.

Building Salt Lake City Walking Tour

Experience the wide variety of building stones used for building downtown Salt Lake City on this seven-block interactive walking tour curated by the state Geological Survey. Construction materials range from 2.5 billion year-old Precambrian black granite to Quaternary-age travertine.

Utah Department of Natural Resources Map & Bookstore

1594 West North Temple, Salt Lake City

One of the best places to pick up geologic and topographic maps, hiking guides, birder lists and guidebooks of all sorts in the building's lobby.