Hoop by Hoop with Patrick Willie

A Navajo storyteller found his purpose in hoop dancing. Now he’s using his platform to amplify the Native voices of a younger generation.

For more than a decade, Patrick Willie has been posting videos to his YouTube channel. At first, the Orem native filmed himself developing his hoop dancing routines or competing at the world championships. Along with behind-the-scenes moments from his dance performances, Willie included cultural facts to explain Diné (Navajo) culture.

Over the years, the videos took a more distinctive, humorous turn. “I wanted to try a different style of video, my version of ‘America’s Funniest Home Videos,’ Native American style,” Willie says. “That was something I had never seen.” And so he launched the “Natives React” series, with friend and cohost Jacob Billy.

The series became a chance to comment on the indigenous stereotypes they observed in mainstream culture. They began inviting guest commentators to join their videos, always aiming to speak to both Native and non-Native viewers. Willie says: “I get comments all the time that say: ‘That was a funny episode. But also I learned a lot about your culture.’”

Fast forward to 2021, when Willie’s channel had attracted more than 146,000 subscribers, boosting him to the forefront of Native American YouTubers. That earned him recognition from YouTube on International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (August 9). “We’re shouting out @patrickisanavajo, who amplifies Indigenous experiences and celebrates Navajo culture with his channel,” read their Instagram post.

Willie aims to use his videos and his hoop dancing performances to tell positive stories about Native culture (Read: “Native Nations in Utah”). He won’t include crude humor or adult language in his videos, and he won’t include any depictions of Natives drinking or using drugs.

Along the way, he’s become part of an informal collective of Utah’s young Native American artists who serve as digital cultural ambassadors. “They’re really comfortable with the format, and they know how to use that media to promote Native culture,” says Dustin Jansen, director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs. “They feed off each other and encourage each other. They help each other out a lot.”

The Distinctive Comfort of Native Humor

When viewers talk about the “Natives React” videos, they regularly underscore the series’ humor, which one viewer labels as “comfortable.”

“Patrick makes it okay to laugh at ourselves,” says Isaac Madson, a subscriber who’s the communications director for the Rural Utah Project, an advocate for the state’s underrepresented communities. “As a person [who] was born and raised on the Navajo Nation, when I watch his videos I feel like I'm hanging out with my cousins or friends from back home.”

Non-native people aren’t always aware of the distinctive nature of Native humor, says Caitlin O'Reilly, a content creator from Casa Grande, Arizona.

“That kind of humor isn’t really seen in the mainstream media, and so it is nice to have a place to go that just gets us,” says O’Reilly, who subscribes to Willie’s channel. “In addition to being entertaining, the content is also educational by highlighting other Natives doing amazing things in their community, as well as certain issues that we face.”

Willie also uses his audience to boost the talent of other Native content creators, such as Jo James, who lives on the Yakima Reservation in Washington state.

“There isn’t anybody I know who makes videos like his,” says James, who posts videos as a creative outlet while juggling graduate studies. “He does a really good job at balancing the funny parts of Rez life with serious subjects. It’s not only his success, but his voice within a bigger platform, that is very important for Indigenous people.”

"There isn’t anybody I know who makes videos like his. He does a really good job at balancing the funny parts of Rez life with serious subjects. It’s not only his success, but his voice within a bigger platform, that is very important for Indigenous people."

– Jo James, Native Content Creator

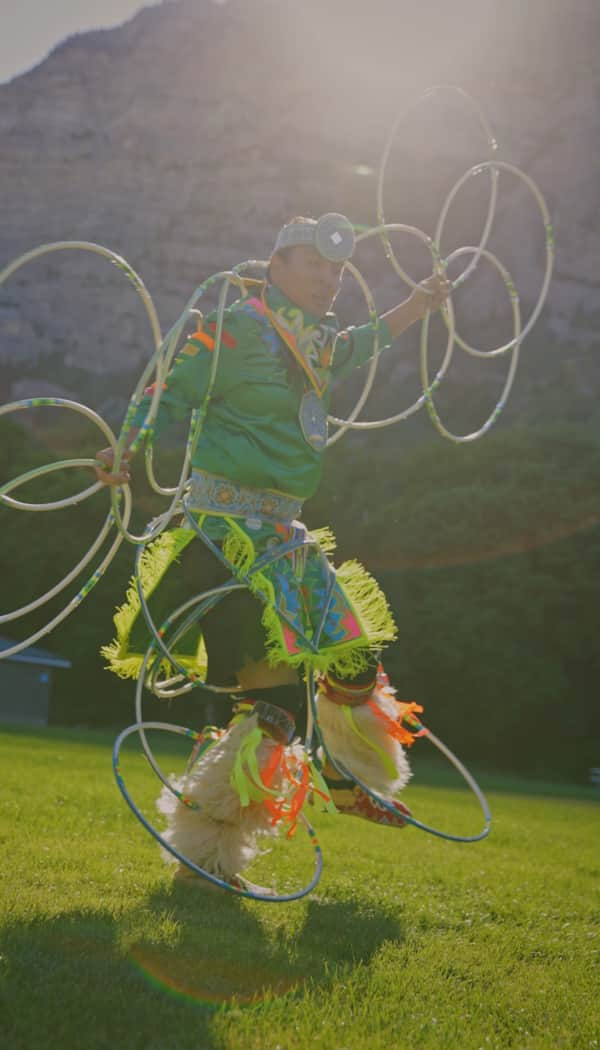

Representing the Circle of Life

With the stories he tells in his hoop dancing routines and in his videos, Willie aims to be the kind of role model he didn’t have growing up as a “city native” in Orem.

His parents were raised in New Mexico on the Navajo Nation, but there were just a handful of other Native students in the school Willie and his sisters attended. He started fancy feather dancing when he was young, but as a kid dancing was just an occasional thing. “Growing up, we knew a little bit about the Navajo lifestyle and culture but not a lot,” he says. Kids teased him for his long hair, while mistakenly assuming he was Hispanic.

About a decade ago, when he was in his 20s and studying math at Utah Valley University, he rediscovered hoop dancing. He began studying with mentors and committed to rehearsing daily. Dancing became a way for him to more deeply understand his heritage, and to share it through teaching weekly lessons. (Read: “Art Keeps the Native American Culture Alive”)

“He’s letting kids know how far your culture can take you,” says Jansen, because dancing has taken Willie all over the world. He’s performed in China, Australia, Fiji, France, Canada and all across the United States. In 2020, he earned sixth place in the World Hoop Dancing Championships at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, continuing a string of six top 10 finishes.

“The world,” one grade-schooler answers, loudly, so he can be heard over the Native American drum class in the far corner of the cafeteria here at Orem’s Mountain View High School. Another dancer adds: “The circle of life.”

“What do we dance for?” asks Willie, who has been teaching classes for 5-to-12-year-old students at this school for nearly a decade.

“For our families,” one young dancer says.

Other answers: “For our friends.” “For our parents.” “For our school.” And finally: “For our ancestors.” (Read: "Nourished by the Land: A Shoshone Perspective")

On this cold winter night, students watched as Willie rode up to class on his bike. After teaching four dance classes, Willie biked home, too, because he loves cycling, but also because he doesn’t own a car. Riding his bike offers Willie the chance to model healthy living in a culture that often faces health challenges such as diabetes. “He’s the future of Indian young people,” says his boss, Jeanie Groves, who coordinates the Alpine District’s Title VI Indian Education programs.

Willie likes “to think outside the hoop,” inventing movements inspired by nature. He’s perfected a unique pickup of his first hoop, where he appears to jump inside the circle and lift it with his feet. “There’s not anybody else I know of that does that,” says Terry Goedel, one of Willie’s mentors. Goedel, a world-champion California hoop dancer, is a legend in the Utah dance community, and his son often dances and teaches with Willie.

Native American hoop dancing is particularly popular in Utah, thanks to the strength of the American Indian studies programs at Utah Valley University and Brigham Young University, and the prominence of BYU’s Living Legends performance group. Also significant is the Intermountain All-Women Hoop Dancing Competition, the only all-women hoop dancing competition in the world — which was launched at Salt Lake City’s This is the Place State Park.

“He’s totally in it for the kids,” says Amy Ieremia, a dancer who previously taught at Mountain View, and whose children now take Willie’s classes. “It’s all about passing on what he knows.” (Read: "Paying Rapt Attention to Utah Shoshone’s Winter Storytelling Traditions")

She adds: “My kids love to watch his YouTube channel. They quote it.”

"Native American hoop dancing is particularly popular in Utah, thanks to the strength of the American Indian studies programs at Utah Valley University and Brigham Young University, and the prominence of BYU’s Living Legends performance group."

“Don’t call this a costume,” Willie often tells students, because American Indian dancers aren’t characters playing dress-up. “We prefer ‘outfit’ or ‘regalia.’”

Photo: Samuel Jake

‘Don’t Call This a Costume’

One of the first original moves Willie created involves spinning four hoops on his arms, then adding a fifth hoop spinning on his leg. “When I do that move, I hop on one foot, and then I dance backwards,” he says. A friend said he looked like a hummingbird. “And then I found out the hummingbird is the only bird that can fly backwards, which adds another layer.”

In 2017, Willie launched a service project for Native American Heritage Month in November, borrowing the idea from one of his hoop dance heroes, Tony Duncan. Willie volunteered to present free dance performances at local schools, and in one month, Willie biked more than 200 miles to perform at 27 schools, including one four-performance day.

In his dance presentations, just as in his videos, Willie talked about contemporary American Indian culture in an effort to combat what he calls “TV stereotypes.” There are 562 tribes in the United States, and all tribes are different, he told students. “Don’t call this a costume,” he says, because American Indian dancers aren’t characters playing dress-up. “We prefer ‘outfit’ or ‘regalia.’”

Storytelling Outside the Hoop

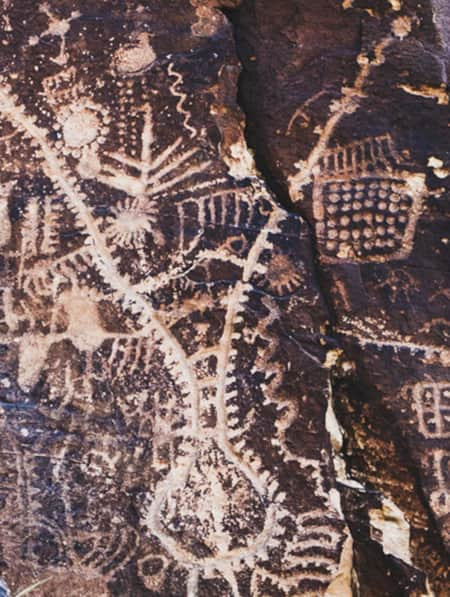

Willie’s most popular video showcases his original moves as he dances at some of Utah’s most iconic locations — at the State Capitol, in Provo Canyon, on the shores of the Great Salt Lake and in Monument Valley.

It’s worth watching to see Willie’s sophisticated hoop movements and his colorful regalia in contrast to Utah’s blue skies and red rocks scenery.

But the most fascinating part of the video is the ending, which highlights the joy of Patrick Willie. He’s dancing on a beautiful fall day, and as he steps on a hoop, he flings a handful of hoops over his head, a move he’s performed thousands of times. But this time, one hoop escapes to lodge high in the tree leaves above him. It’s a dramatic moment, and the video keeps going as Willie stops dancing to look up for his missing hoop.

Hoop dancing reflects life, and things don’t always go as you expect. Maybe police officers will stop you when you’re filming a video for Native American Heritage Month. Maybe you’ll have a conversation about unity with protestors after dancing at the Utah State Capitol. Or maybe you’ll bike two hours to film on the shores of the Great Salt Lake, and you’ll find yourself with an audience of fishermen.

“When you drop a hoop, you have to adjust on the spot,” Willie tells his dance students. “When you adjust, you’re changing the story."

In the video, the camera watches Willie as he laughs and keeps laughing as he walks out of the frame. The story of this Utah dancer has just changed, and it’s a moment worth watching over and over and over again.