Ancient Pictographs, Petroglyphs and Timeless Mysteries

The secrets of Horseshoe Canyon

The National Park Service website for Horseshoe Canyon issues several direct warnings: “Do not rely on a GPS unit to guide you to Horseshoe Canyon. Use a map instead”; “Be prepared for hiking on uneven terrain, over steep rocky areas and slogging through sand” and “There is no water above the canyon rim, and water sources are unreliable within the canyon”. Indeed, this inhospitable spot, which is technically part of Canyonlands National Park but isolated from the three major park districts, doesn’t come with creature comforts like hydration sources, cell reception or visitor center.

In other words, exploring Horseshoe Canyon isn’t for everyone. First of all, the effort to get there is an adventure in itself: After driving at least 90 minutes from the closest town of Green River (and 2.5 hours from Moab), you’re looking at another long stretch on dirt roads, anywhere from 30 to 47 miles, depending on the route. At the canyon itself, it’s a seven-mile round-trip trek to the Great Gallery (more on that below), which starts with a steep 780-foot descent — meaning that you’ll have to grind up that grueling stretch at the end of your hike.

But those efforts make the reward — namely, the chance to see up close some of the most significant pictograph panels in North America — even more noteworthy.

Modern-Day Evidence of Ancient Storytelling

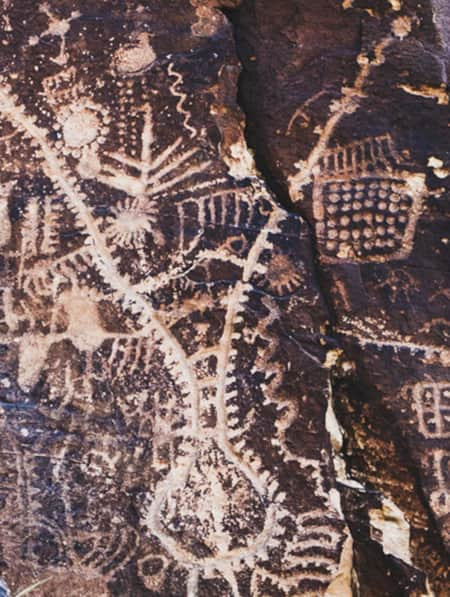

The Native Americans settling and traveling through Horseshoe Canyon left few clues behind, but artifacts found in the canyon date back as early as 9,000 B.C. The appeal for many modern-day visitors, however, is the remarkably well-preserved pictographs on the canyon walls, painted and etched sometime between 2,000 and 5,000 years ago.

Nomadic hunter-gatherers who once used this canyon as a seasonal home left behind images of human-like figures, animals and other objects on the sandstone walls — creating what archaeologists consider the largest display of Barrier Canyon Style pictographs (painted on stone) and petroglyphs (images etched into the stone). Several displays of ancient pictographs and petroglyphs adorn this three-mile stretch of Horseshoe Canyon, the most famous of which is a panel known as the Great Gallery.

Finding the Elusive Canyon

For my friend and me, the adventure to Horseshoe Canyon started the evening prior to even

"I can’t help but gasp as the first glimpses of the Great Gallery come into view, shrouded by a string of cottonwood trees."

After sunset, finding the turn off Highway 24 proved no easy task. We caught sight of an unsigned dirt road that seemed likely but decided not to press our luck until morning, so we made sure we were on BLM land and found a spot farther up on the road to camp overnight. By daylight, we scoped out things again. We soon reached an intersection with another promising dirt road and decided to check it out. A dust cloud appeared in the distance: another vehicle. We flagged down the truck, which fortunately had Utah license plates, and the couple inside assured us that we had indeed found the road to Horseshoe Canyon. They told us to keep a lookout for the fork in the road after about 25 miles.

Sure enough, an information kiosk eventually appeared in the middle of the desert with directions for the remaining seven miles to the west rim trailhead.

The Journey to the Great Gallery

We don’t talk as we take our first steps down into the canyon. After all, these are the Utah canyons I know and love, and I prefer to admire their beauty in silence. Light tan sandstone forms into domes that span out over the horizon. Sheer vertical walls of deep orange Navajo sandstone marred by streaks of black varnish give way to layer after layer of eroding rock, each one stretching farther into the middle of the canyon as they descend. Toward the bottom, the rock layers crumble away, creating small canopies of shade and cavernous amphitheaters. A wash of gold sand, soft as silk, snakes its way through the canyon floor. Intermittent swatches of pale green — cottonwood trees, sagebrush, rabbitbrush — dot the warm landscape in subtle contrast.

After descending into the canyon, the hike becomes less of a singletrack trail and more of a walk through the sand in the direction of the famous pictographs. The park service estimates a 7-mile hike to the Great Gallery and back, but my GPS clocked us in at nearly 10 miles total.

Our pace is slow as we constantly scan the rock walls for painted images of humans, animals or ancient mysteries. We’re joined by few others on the trek, adding to the sense of discovery.

Then, I can’t help but gasp as the first glimpses of the Great Gallery come into view, shrouded by a string of cottonwood trees. I’d seen other pictographs, including the multiple panels along the way in Horseshoe Canyon, but none were nearly as impressive as this one in terms of size and stunning clarity of color. Stretching 200 feet across the canyon wall, this collection of vibrant red and bright white anthropomorphic figures is simply remarkable.

Secrets in the Stone

There’s a certain camaraderie among the small group of onlookers as we come and go, gathering around a small stone bench to take in the full view of the Great Gallery. Most art galleries require visitors to find a parking spot and pay an entrance fee. This one requires driving through the dirt and slogging through the sand for hours. We are here intentionally — we didn’t just stumble upon this spot or hop out of the car at the first trailhead on a national park scenic loop. Those who make their way here are genuinely curious about the pictographs, the people who created them and the history of the canyon.

We take turns looking through the park service binoculars to study the details in this remarkably intact panel. The volunteer park ranger shares what she knows about the natural and human history of the canyon. What she — or anyone, for that matter — can’t tell us for certain is what these pictographs mean. Everyone seems to ask this question, and each time the answer remains the same: It’s open to interpretation; there’s really no way of knowing for sure.

To me, that’s just another part of the adventure and allure of this fascinating place.

Trip Planning & Logistics

Weather can quickly change the dirt access roads from two-wheel-drive to four-wheel-drive conditions. The roads may become impassable during storms. Check the road conditions online, or call (435) 259-2652.

NPS offers a basic map showing the access roads to Horseshoe Canyon. More detailed maps are available for purchase.

Primitive camping is allowed at the trailhead, where there is a vault toilet but no water.

Pets are not allowed on the trails.

Ranger-guided hikes are offered most weekends in spring and fall. Call the Hans Flat Ranger Station at (435) 259-2652 for arrangements

Always respect the archeological sites. Pictographs and petroglyphs are an important part of our human and national heritage and can be fragile. Follow Leave No Trace principles so future hikers have the same experience and sense of discovery that you do.

Trail Guide

Difficulty: Moderate

Distance and elevation gain: 7-9 miles round trip and approx. 1,000-2,000 feet. Distance and elevation varies based on the route you take.

Trail type: Hiking

Multi-use: No

Dogs: No

Fees: The area is part of Canyonlands National Park (which has fees).

Seasonality: Spring and fall are the best times to hike in Horseshoe Canyon. The trail is accessible in summer and winter, though weather conditions are not ideal.

Bathroom: Vault toilet at the trailhead

Where to park: Horseshoe Canyon West Rim Trailhead (Canyonlands National Park)

Trailhead GPS coordinates: 38.474399, -110.200335

What's Nearby

-

Capitol Reef National Park

Even considering Utah’s many impressive national parks and monuments, it is difficult to rival Capitol Reef National Park’s sense of expansiveness, of broad, sweeping vistas, of a tortured, twisted, seemingly endless landscape, or of limitless sky and desert rock.

-

San Rafael Swell

San Rafael hikes and bike rides offer unique terrain and jaw-dropping scenery. Learn about the area’s trails and start planning your trip!