A Walking Tour of Helper, Utah

Historically, the east side of Helper’s main drag was the respectable side. The other side had a seedier past. According to legend, tunnels between the two sides helped locals deceive law enforcement during Prohibition by moving illegal goods and services underground. The road that demarcates the commercial district points due north and seems to crash into the Book Cliffs, a rocky escarpment of shale and sandstone in a gradient of gray to red.

In a certain light, these cliffs shine.

For a few months in 2016, Helper, Utah, looked a little like its old, old self: Main Street, lately torn up, was a dirt road wanting only for hitching posts or early internal combustion engines rumbling around on four oversized bicycle tires. Helper was getting a makeover, adding polish and curb appeal to this friendly, walkable town known for its eclectic art scene, great coffee and a heritage that proudly sits right on the surface. Exhibit A: the 18-foot-tall fiberglass coal miner “Big John.” Beneath the surface, would the excavation reveal hidden tunnels connecting the two sides of the town?

Photo: Dean Krakel

Buried Treasure

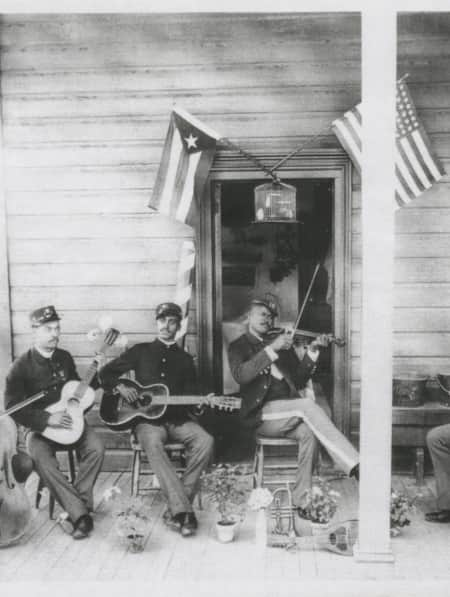

In the Western Mining and Railroad Museum, low-fidelity, muffled jazz and blues drift through the old Helper Hotel wing. It’s all here: major events such as the United Mine room, Castlegate Mine explosion room and personal mining items such as lanterns, lamps and bird cages. Butch Cassidy even makes an appearance.

When we visited, then-museum director James Boyd walked us through the town’s history, from the Denver & Rio Grande survey that turned up abundant reserves of coal to the arrival of narrow gauge, standard gauge (gauge refers to the spacing of the rails) and the intertwined growth of the mines and railyard. Drawing on the momentum of America’s third wave of immigration in the 1890s, agents of the mines successfully recruited workers in Europe and Asia such that Helper became a vibrant melting pot in the heart of Utah.

Boyd adds, “Of course, there were also a number of Hispanics who followed a mining route up from New Mexico into Colorado to Utah and most of them had become citizens in the Gadsden Purchase back in the 1850s. I asked a Hispanic [visitor to the museum] once where he came from and he said ‘I’m an American. I’ve always been here. My family goes back to the 1600s.’”

"Helper was getting a makeover, adding polish and curb appeal to this friendly, walkable town known for its eclectic art scene, great coffee and a heritage that proudly sits right on the surface."

Photo: Dean Krakel

Photo: Dean Krakel

Photo: Dean Krakel

One of the better-known items in the museum is a photo that depicts a child miner: a toddler’s face of cherubic cheeks and furrowed brow beneath a miner’s hat and dressed for work with tiny lace-up boots, tobacco pipe and a pickaxe as tall as the boy himself.

Across the street from the museum on the warming spring day, a cluster of men with metal detectors scanned the roadside. The group jumped at the opportunity to search for artifacts of the American West before the road and sidewalks were re-installed. Don Harsh, president of the Utah Treasure Association, and Dave Kyte, the group’s founder, revealed the hunt hadn’t yet turned up much. One of the men drew out a die-cast half-shell of a kid’s toy gun.

As the group searched, they spoke fondly of a recent opportunity to hunt the grounds of the World War II CCC & POW Camp in nearby Salina. The town recently opened a museum to mark the site of the camp and document the infamous Midnight Massacre where an embittered — declared insane — American soldier opened fire on the German prisoners.

For a history buff like Kyte, the pursuit is more than a pastime: It helps preserve history. The organization donated everything they found to the Salina Museum. These relics, no matter how small, are important. They help preserve a fading hyperlocal rural identity. Restoration expert Gary DeVincent also looked at Helper and clearly recognized the depth and potential of the old mining town's identity when he got to work renewing a set of vintage gas stations. The newly renovated service stations don't pump fuel, but they do tap into the town's historic past and artistic present in a way that is unique to Helper. Somehow, they just fit in here.

Happiness Within

Nostalgia permeates Helper. Visitors and artists alike seem drawn to a reflectiveness of the rural setting. For artists, Helper provides a space within which creators can dig deep within themselves and discover or sharpen their artistic identity. A number of galleries line Main Street and the city and county unite behind the Helper Arts, Music and Film Festival, which in 2018 enters its 24th year, August 17–19 (read: Utah Female Artists Explore the Sublime Through Art).

Many credit artist David Dornan for recognizing the town’s potential and helping to spur its renaissance. Today, the former University of Utah professor serves on the city council and is helping oversee efforts to position the town as an outdoor recreation hub, including a Price River restoration project, the naturally shaded Helper Parkway, and increased connectivity to ATV and bike trails.

Happiness Within is not just a feeling here. It’s an oasis of great coffee in central Utah, a welcoming shop with an upbeat vibe that builds from and feeds the unique community. As I sip espresso and gaze out across the street of packed sand, the image of the tiny coal miner, which Boyd said was staged, feels right at home. It's clear that mining was backbreaking, sometimes deadly, work. But the work helped families build lives. There are senses of humor, art, posterity and desperation playing off each other in the photo; it seems to say this is not precisely the harsh reality, but it’s not far off. Boyd reminded us that the major mining disasters would take whole families, generations of men working side by side. In all, 1,351 died.

Helper was named after the team of “helper” coal-powered steam engines that assisted freight trains up the neighboring canyon and over Soldier’s Summit. Powerful diesel engines mean we no longer need the Helper of times past, but we still need small towns like Helper — towns with a beating heart and a will to persist by evolving their identity; towns that outgrow their old work clothes but refuse to grow old. Helper reminds us of our younger selves and our younger nation. This is where we came from. Helper might still be that young coal miner in the photo, only now we can appreciate him for what he evolved into: humanity and art mined from history but with an unwritten future still ahead.

Explore More

-

Fishing Scofield State Park

Scofield State Park is a peaceful, scenic reservoir with an uncanny ability to produce big fish in quick fashion.

-

Helper

Settled in 1881, Helper was named after the team of “helper” coal-powered steam engines that assisted freight trains up the neighboring canyon and over Soldier’s Summit; the city was created because of and for the coal industry. Though the tracks are still integral in the town’s DNA and even more-so, history, its identity has changed.

-

San Rafael Swell

San Rafael hikes and bike rides offer unique terrain and jaw-dropping scenery. Learn about the area’s trails and start planning your trip!