A View From the Past

Reconstructing forgotten history on the Transcontinental Railroad Backcountry Byway

It's not a view for everyone. But out here, it's Christopher Merritt's favorite. He points west toward the Grouse Creek Range and south to Terrace Mountain. There are no buildings. No cell phone towers. The natural viewshed is totally intact. It's maybe not beautiful in the classical Utah sense. But Merritt is the Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer at the Utah Division of State History. He sees things that others don't.

Some remaining fragments from the byway.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

The view out there isn't for everyone, but for those who choose to go and see, won't regret it.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

Merritt can reconstruct and interpret a site’s demography from the tiniest pieces.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

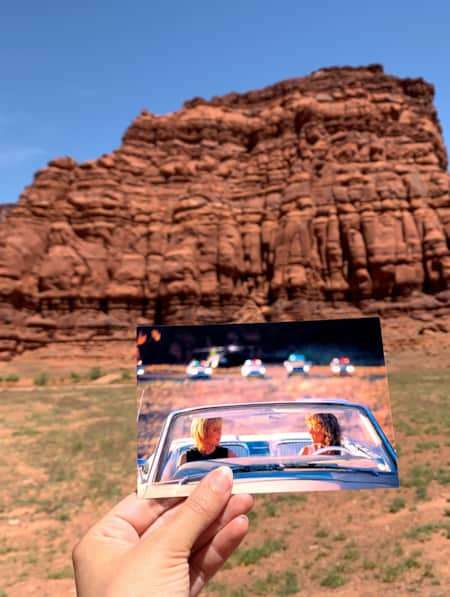

Ray Kelsey (left) and Christopher Merritt (right) use a photo to give evidence of history.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

Trestles of wood cut from the Sierra Nevadas and lined with crossties cut from the Raft River or Uinta Mountain ranges still stand.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

Terrace Cemetery all but vanished after the shorter line was completed across Great Salt Lake.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

This whole experience out on the Transcontinental Railroad Backcountry Byway is not for everyone, and not just because a high-clearance vehicle is required for some stretches. This is a rugged, get-lost-on-the-planet desert experience.

It is safer, then, with two vehicles — just in case you drive over an old railroad spike.

That’s possible because more than 100 years since the line of the world's first transcontinental railroad was unceremoniously dispatched for a quicker cutoff across the Great Salt Lake (save for a few monthly trains through 1942), fragments and ghosts of that engineering "Moonshot" remain scattered across the playa. With Merritt as our guide, the fragments become whole.

The ghosts get identities.

•••

Like the bits of pottery Merritt interprets along the backcountry byway, the Great Salt Lake is a remnant. The shallow, terminal lake spreads across northeastern Utah unmatched in size between the Pacific Ocean and the Great Lakes. For good reason, the lake captures the imagination of visitors. We are several miles west of the retreating shoreline of the Great Salt Lake, near the ghost town of Terrace. The flats of sagebrush and yellowing grasses gently rise to low ridgelines beyond which mirages and larger ranges create a sense of depth. On a clear day, you can see the southern Wasatch Mountains, 150 miles to the southeast. At quick glance, it's a vacant place.

It’s looked this way since Lake Bonneville fully receded, a lake whose ancient shorelines visibly terrace the distant hills. Moving with the seasons, Western Shoshone people drew sustenance from the land from hundreds of years of bioregional knowledge about the Great Basin ecosystem, whose sparse valleys are punctuated by ranges of relative abundance — if you know where to look.

One thing is certain: It's all horizon. Ray Kelsey is an outdoor recreation planner for the BLM who first came out West for college. He didn't realize it until visiting home back East that it's strange to him not being able to see the horizon. We Utahns grew up with horizons — and sunsets. But it's more interesting than that:

"Utah is the crossroads of the west from a transportation standpoint. It's also the crossroads of the west ecologically. There are five ecoregions and it's pretty amazing to have that kind of diversity."

European explorers with locally familiar names like Bonneville and Ogden trapped, traded and explored their way across these ecoregions in the early 19th century. The land was still Mexican territory in 1847 when pioneers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints arrived. In 1849, Howard Stansbury set out with the task to scout potential lines for a transcontinental railroad. And that brings us to the present, 1869, where in Utah’s West Desert an “army” of Chinese laborers support a team of Irish track-layers under the watch of Central Pacific Railroad executive Charles Crocker.

The roughly six-year, 700-mile journey of the Central Pacific from Sacramento to Promontory, Utah, is well documented. 2019 marked the 150th anniversary of the driving of the last spike. Until recently, though, it was largely heralded as the accomplishment of white men: Crocker, Stanford, Huntington, Hopkins, aka the Big Four. We lauded the grade, cuts and fills — and the pace at which they were ultimately built — as feats of ingenuity backed by political deals, financial wrangling and land incentives. A closer inspection of the former encampments and townships along the former line reveals a richer heritage.

•••

The road is rough at times, tempering the pace of travel. But at 15-20 mph, we experience the landscape at the speed of steam. Every stop unveils a range of stories from the shards, sherds, fragments and pieces. Merritt can reconstruct and interpret a site’s demography from the tiniest pieces.

A thick, grayish piece of pottery held soda water or mineral water and was made in Germany or England. It’s thick and heavy to handle the carbonation. A piece of deep-brown glazed ceramic contained soy sauce or maybe vegetable oil and was used by Chinese workers. Looking more closely at another piece, Merritt sees the fingerprint of the potter is still visible — the maker’s mark. There is also fine China and evidence of Japanese pottery for cooking and serving from a later wave of laborers along the line. The paraphernalia from a Chinese opium den is also present, and the idea of discovering a wall of a tin that held opium sends the group of us on the tour on a treasure hunt across the old town site. And, yes, there are also fragments of the bottles that held the Europeans’ whiskey.

But if you really want to light a fire within Merritt, ask him about the Mormon pottery — he wrote his thesis on the subject

Further along, we stop near a collection of old railroad ties and observe the rail fastening system by pushing a spike through a rusty plate. The pieces are returned to the ground where they were found.

There are also relics of the big steam locomotives that powered the endeavor. At one stop, Merritt gathers interlocking pieces of the firebox from inside the steam engine where the coal was burned to produce the heat that boiled the water that made the whole endeavor possible:

“Trains really needed the fresh water. People could drink whiskey,” Merritt said. “Water trains would fill water tanks. Next train would drink it. Everything is connected to water somehow. The railroad was about creating the shortest distance between A and B while maintaining the grade and access to fresh water.”

Of course, growing populations did require a source of water. And this is the West Desert.

The ghost towns of Western civilization in this unforgiving landscape are remarkable. Perhaps only the city engineers knew the fragility of the water source for the line’s largest town, Terrace. (It was an underground aqueduct from springs in the Grouse Creek Range using hollowed-out redwood logs.) At its peak, Terrace reached nearly 1,000 residents, many of whom were likely Chinese, excluded from the census. The railroad town and its population attracted a chain store, imported trees, library, opera house, pleasure garden, a couple of hotels, a school, a public bath and even a justice of the peace who, according to the shot-up interpretive signage at the site, also ran the saloon.

For Merritt, that rich history offered one of the coolest things he’s found on public lands: Evidence of a hotel chandelier at Terrace in the form of a dangling prism.

•••

Out here, even the cemetery has lifespan. As I interpret the sign, the Terrace Cemetery died circa 1910. With its destiny completely tied to the railroad, Terrace all but vanished after the shorter line was completed across Great Salt Lake. Merritt and Kelsey have aerial terrain maps with outlines of the former city showing the lay of the land and we can physically walk through the concave dugout of the turntable and see the outlines of roundhouse stalls. Presence through absence.

Earlier on the trip, we walked the length of the Peplin Cut, a jagged and narrow passage through a low-slung hill spotted with Russian thistle, the forebearer of tumbleweed. The Central Pacific created the cut with dynamite, horses, shovels and manpower. It was one of the last major roadblocks before the climb to Promontory, which almost seems minor looking east and west across the hundreds of miles of slow, rolling, arid terrain.

The nation was right in the middle of Civil War Reconstruction when it embarked on a massive engineering effort through challenging territory that also encroached on tribal lands. The completion of the project would have a global economic impact and hasten the settlement of the country with ease of movement, but also because it improved the army’s ability to move supplies for use against Native peoples. Standing near the cut, these are some of the credentials that Ray Kelsey reflects on and that anachronistically gave the First Transcontinental Railroad the superlative “Moonshot.”

If the 150th anniversary of the completion of the transcontinental railroad was different from the 100th anniversary it was in better recognizing the laborers who built it and acknowledging the people who were displaced to create the right-of-way.

“We’re really seeing something new: A more holistic story. We value sites on a different level. Trash is part of the workers’ story because it reflects their lives. Now we are pursuing a deeper, more nuanced and culturally sensitive version of our heritage and paying attention to details we previously ignored,” Merritt said.

Where relics of the old railroad towns were looted or taken as souvenirs on tours in 1969, today we shake our heads at the lack of respect, knowing full well the tragedy of cultural vandalism is far from behind us. So much has already been lost, but for well-prepared visitors with a passion for history and predilection (or patience) for Great Basin topography, stories abound out here.

Meanwhile, trains still run across the Lucin Cutoff, now a causeway that slashes Great Salt Lake in two. At our completion of the Transcontinental Railroad Backcountry Byway, it is time to return to the Wasatch Front. On the drive home, I look west off the Interstate toward the lake and the jagged ridgeline of Antelope Island and marvel at the new appreciation for a place I’ve seen the sun set over since I was old enough to remember.

Ready to venture out on your Transcontinental Railroad adventure? Find a detailed map here.

-

Brigham City

Brigham City's Main Street archway proclaims "Gateway to the World's Greatest Wild Bird Refuge." Brigham City boasts a small-town feel with big-city amenities like comfortable and affordable hotel rooms, deluxe suites, and beautiful golf courses.

-

Golden Spike

Visit the Golden Spike National Historic Park to relive the history with exhibits and demonstrations, and take in the beauty of the surrounding Great Basin Desert and nearby Great Salt Lake and Spiral Jetty.