Arrive by Train

Northern Utah’s Golden Spike Country and railroad history are much bigger than the golden spike.

But the city of the future was not destiny. Corinne today is not a place most Utahns have heard of, let alone visited. I stood there 149 years later, on a May afternoon. At the center of town was the popular Golden Spike Burgers, where my daughter Juliet and I had just finished off a meal; she had a burger and I had a chile verde burrito. From what I could gather, the town’s most prominent landmark was the giant golden spike in the roof of the restaurant, which, along with the restaurant’s name, was a nod to the much better-known attraction to the west, the Golden Spike National Historic Park, where the Transcontinental Railroad was linked a few weeks after the Hell on Wheels burned through Corinne.

Indeed, we were on our way to that meeting place in the desert. We had packed bikes and taken a train and bus from our house in Salt Lake to the northern reaches of the Wasatch Front, riding through the Bear River Valley, our ultimate destination the annual reenactment of the driving of the last spike at Promontory Summit.

This was a pilgrimage of sorts. Juliet and I had family history here — beginning as a small child, I was told that one of my direct ancestors was part of the last spike ceremony. An old photograph of him had hung in the hallway outside my bedroom. It showed a thoughtful-looking, white-goateed man sitting behind two bald Asian men, who, my mom said, were Chinese rail workers. But I didn’t know who this was, or what his job was. I had never even been to Promontory.

It was also a trip into the past and future of Utah. A remote spot had sent the Wasatch Front on a growth trajectory 150 years ago. Now Promontory was within shouting distance of the expanding edge of a metro region predicted to grow to 5 million people by 2050. Then, as now, our population occupies a thin strip of fertile land, with the growing question of how we can sustain it — to suspend the disbelief of a thriving civilization here.

"We could see the two locomotives nose to nose in the huge valley. We were at the top and felt the connection to the east and to the west."

The final "champagne" photo reenactment.

Photo: Andrew Dash Gillman

The past, present, and future — all visible from Salt Lake City's Front Runner Station.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

Exploring history at Ogden's Union Station Utah State Railroad Museum.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

Heading to explore downtown Ogden from Union Station.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

The iconic arch welcomes travelers to Brigham City, the Gateway to the World's Greatest Wild Bird Refuge.

Photo: Marc Piscotty

As we found, the clang of the Golden Spike resounds far throughout this corner of Utah, in a region still feeling the effects of the meeting of the rails. Confronted by the expanses of the Great Basin, Golden Spike reminds us that we have the same challenges today that were there at the beginning. As Corinne knows too well, the Golden Spike country of today straddles land both urban and empty, fertile and ruthlessly rugged.

Go North

It made sense to begin our journey on a train platform, albeit a modern one. On a bright morning a few days before the Golden Spike celebration, we left our house and rode a few miles to Salt Lake City’s North Temple Station. FrontRunner, the Utah Transit Authority’s commuter rail service, runs through here on its way south to Provo and north to Ogden.

The Transcontinental Railroad did create cities of the future in Utah — but they were 25 and 65 miles to the south in Ogden and, in particular, Salt Lake City. The scene in Salt Lake was likely what the founders of Corinne had in mind: It was a rush of commuters pouring off the double-decker train in hurried walks to offices in the skyscrapers surrounding the station. Three new residential buildings — hundreds of new apartments and condos — were under construction next to it.

Our bikes parked, our tickets purchased, Juliet and I walked to the edge of the platform and looked at the tracks. There was steel and concrete instead of iron and wood, but it was still rails, spikes, ties and ballast. A noise grew down the line; it was an old U.P. train shrieking by — Union Pacific: Building America, the engine’s battered paint read.

After the Ogden-bound FrontRunner train arrived, we moved north smoothly in the upper floor of the double-decker car. Our booth was outfitted with a table, an electrical outlet and Wi-Fi. Juliet drew while I watched out the window, looking east. The morning shone on alternating patches of green countryside and suburb, the freeway a parallel rush of mobility. In contrast to the fast food and gas stations of the Interstate corridor, along the train line rose three, four, five-story residential and office buildings with names like “City Centre.” Now, the railroad was the new antidote for our freeway-driven growth pattern, a second chance at getting it right.

Weber Canyon came into view, a giant “V” cleaved into the Wasatch wall. I felt us coming into Utah’s train heartland. We crossed the Weber River and curved into the huge rail yard.

Uniting the States at the Crossroads of the West

The Transcontinental Railroad came at a critical time for the United States. At the railroad’s inception, the nation was fighting to keep the union together from north to south. By the time the railroad was on its way to being finished, the Civil War was over, and the union was preserved — and now it was time to link the nation east to west.

Congress authorized two railroads to start at either end of the American West and build as fast as possible to an undetermined meeting point in the middle. The Union Pacific would start from Omaha, Nebraska, and build west along the Platte River through Nebraska and Wyoming Territory. The Central Pacific would begin in Sacramento and run over the Sierra Nevada mountains through the Great Basin eastward. But in the middle part of Utah, the Great Salt Lake and its surrounding mountain ranges posed a major obstacle, and no clear best route presented itself.

Salt Lake City was the only place on the entire route from Omaha to Sacramento with a significant pre-existing white settlement, and as the two railroads raced into Utah territory, Brigham Young was only too happy to help the U.P. and the C.P. work through these last challenging stretches of the road. Young’s Mormon labor forces joined the U.P. and C.P. crews of surveyors, graders, and track layers to overcome Echo Canyon, the gorge of the Weber River, the Great Salt Lake desert and, finally, the grades of the place that was, at nearly the last minute, chosen as the meeting place — the pass in the Promontory Mountains.

And so Utah — and specifically present-day Weber and Box Elder counties — emerged as the theater for the final drama of the national road. It wasn’t just that the golden spike itself was driven in Utah, it was that the whole landscape was overtaken in those final weeks by the two rail companies’ drive to succeed. The country’s ears were fastened to the telegraph, which pounded out every advance and conflict on the lines as they came closer together, the current of American audacity and hubris. This most American of landscapes became the last critical link in the nation.

Welcome to Railroad Country

Rolling into Ogden on the train seemed like how you are supposed to arrive here. After crossing the green, cottonwood-covered sweep of the Weber, we turned into the enormous rail yard and could see downtown Ogden presenting itself. The yard was a museum of all different railroad cars — Southern Pacific, Central Utah, Union Pacific. While Promontory was the place where the lines fused, Ogden became the transfer point between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, and one can understand how the bustle and grand commercial promenade of the city’s iconic 25th Street came to be.

"Rolling into Ogden on the train seemed like how you are supposed to arrive here."

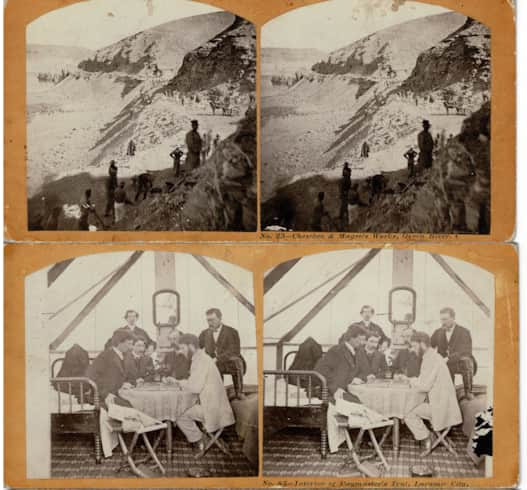

Author Tim Sullivan's great-great-great-great grandfather with employees.

AJ Russell stereographs of scenes of building the Union Pacific Railroad and the interior of paymaster's tent.

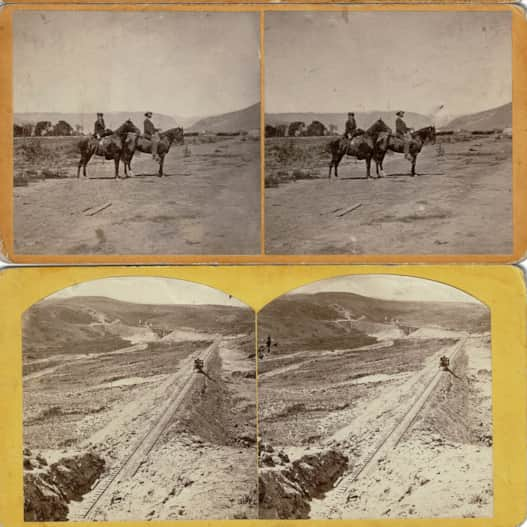

AJ Russell stereographs of scenes of building the Union Pacific Railroad.

The view from the Bear River in Corrine.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

Tim and Juliet ride the "playa," the dry bed north shoreline of Great Salt Lake near Kosmo, a point on the BLM's Transcontinental Railroad Backcountry Byway.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

Replicas of the wood-fired Jupiter and coal-powered No. 119 from the original meeting of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

Photo: Sandra Salvas

We got off the train at the FrontRunner station, but our first destination was the old Union Station next door. This iteration of the station is a massive Italianate terminal built in 1924 to replace the previous station destroyed by fire. (And today anchors 25th Street, which collects a number of local restaurants and shops, coffee, brewing, venues and distinctive old-town character within walking distance of the train.)

We parked our bikes in front and headed into the Railroad Museum, one of four museums the station now houses. What pulled my attention was the museum’s model railroad, which snaked around a network of hallways and depicted in miniature the key Utah Transcontinental scenes — Promontory, Weber Canyon, Corinne, and what became known as the Lucin cutoff, the shortening of the route by bridging across the Great Salt Lake. One of the model scenes showed what may have been the most remote Utah town ever — the small community of Midway, which existed for decades on a man-made island in the Great Salt Lake to house workers maintaining the trestle bridge. The original Lucin bridge had been scrapped in favor of the present-day causeway, but some of the salvaged timbers framed the museum entryway.

After a walk and lunch on Roosters Brewing's sunny patio looking onto 25th Street, we pushed further north. Our next leg was on a bus to Brigham City, which left mid-afternoon from Ogden Station.

“It’s a long ride,” said the driver, helping us load our bikes onto the rack on the front of the bus. “But it’s a nice ride.”

We were now in Golden Spike country. As the bus ran north, we could see its different facets: the frame of I-15, of bedroom communities and jobs. The orchards and farms along U.S. Highway 89, leading into the plane trees and iconic arch on Brigham City’s Main Street. And the desert, lake and, I imagined, the remnants of the obscure Midway Island beyond. Could you still make a good living farming here? I wondered. Were these towns destined to be swallowed by the linear city of the Wasatch Front?

The end of the line was at the north end of Brigham City, a worthy destination in its own right as well as an excellent regional base camp given its proximity to Golden Spike and the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. It was the furthest north UTA will take you on a bus — perhaps a good way to define the edge of the Wasatch Front. Beyond was a small, two-lane country road ambling into the countryside along the base of the Wellsville Mountains. From here we’d be cycling (read: Discovering Box Elder).

The sun was low when we rolled into Honeyville, 10 miles to the north, stopping at a motel at the town’s lone crossroads for the night. The name alone had made me want to visit here. One story had it coming from the wild beehives in the mountains to the east, raided by the town’s first white settlers. Another was that the area reminded the town’s Mormon bishop of the biblical Canaan, a land of milk and honey.

The Photos Don’t Do Them Justice

Before I left on the trip, I had done a little family research. Who was my ancestor at the golden spike ceremony, the man with the white goatee? Was he in the famous “champagne” photo, of men on the nose of each engine raising bottles to toast the meeting? Was he in the bleachers? Was he even really there that day?

My mom had a name — Oliver C. Smith, a.k.a. O.C. Smith. When I found his obituary online, my mom put it together that he was my great-great-great-great grandfather, the originator of a long line of ancestors who lived in and helped build up Rock Springs, your basic Hell on Wheels U.P. town on the Wyoming plains.

O.C. Smith was a railroad man from the beginning. Born in Massachusetts in 1825, he took charge of the construction of a railroad in Uxbridge in 1855. This was the first in a string of jobs in railroads, construction and real estate that took him from Pennsylvania to Michigan and back to Massachusetts.

He didn’t get out west until 1868, when he took the job of paymaster for the Union Pacific. The paymaster is responsible for paying the workers, which was funny, because U.P. President Dr. Thomas Durant was famous for not paying the workers. In fact, the last spike ceremony was delayed two days because Durant’s train en route to Promontory was hijacked by an angry mob of workers demanding their pay (one story has this as a plot cooked up by Durant himself). Nevertheless, O.C. Smith was said to have distributed $5.3 million in payments over the building of the U.P. road from Omaha to Promontory.

He must have known Durant and Grenville Dodge, the former Union army general who was the U.P. chief engineer. And maybe even Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker and the other Central Pacific honchos.

There is still enormous community pride about the Transcontinental Railroad in Bear River Valley towns like Tremonton, where a two-story, sepia-colored mural of the champagne photo lies on the side of a commercial building on Main Street, one of a series of murals downtown depicting important events. At The Pie Dump, where we stopped for breakfast the next day, the chef told us about how bright the colors of the steam train locomotives were, that you’d never know from the black and white photographs.

We arrived in Corinne midday, after a nice ride through the Bear River Valley’s rolling agricultural land. Corinne was clearly a different kind of town from the Mormon farming hamlets like Honeyville; Corinne’s blocks and buildings gave a wide berth to the railroad. It was one of the few Utah towns with a “Front Street,” where mayhem had reigned at places like the Montana House. Now Front Street, with well-kept homes and lawns, looked like any other street in a small town. The tracks still ran through Corinne but faded out after a spur to the Utah Onion Company, the adjacent Walmart distribution center asserting what now counted as freight. The town had a bar, Mim’s, next to Golden Spike Burgers, but it likely did not serve sagebrush whisky.

We were now on the U.P. grade as it headed west.

A Place That Makes Sense

Past Corinne, the blooming desert gave way to the raw desert. We skimmed the northern edge of the Great Salt Lake shorelands and saw a heron and several red-winged blackbirds in the marsh. The road rounded the tips of bare mountains and around the bend of one of them, the most enormous vehicle I have ever seen was delivering a rocket motor to the nearby Northrop Grumman Innovation Systems (formerly Orbital/ATK Aerospace) complex.

I could also see the summit. It was a depression in the Promontory Range, visible from far across the basin. Eventually, I could see what I thought were the railroad grades twisting up the hill. I could tell we were nearing the site where the nation first came together by rail.

As the Union Pacific and Central Pacific approached a meeting point, chaos ensued. Congress had not yet determined the exact joining point, and so the railroads, each hustling for every foot of the line it could claim, eventually began grading in parallel to one another. The crews were often working within a few feet of one another. The Irish crews of the U.P. harassed the Chinese crews of the C.P. — throwing frozen dirt clods, hurling pickaxes and setting off explosions near them. The railroads’ leadership bet each other in how much track could be laid in one day. In the final days of the race to Promontory, the C.P. crews put down 10 miles in one day — laying track at the pace of a person walking. As Stephen E. Ambrose writes, “The end of track…was the only place that mattered.”

The parallel grades are no more spectacular than on the climb up to Promontory, where they snake around each other on their way up the dramatic 600-foot climb to the summit. The crux of this climb was the crossing of a large ravine, which each of the railroads handled differently. The U.P. built a giant trestle bridge, “hastily,” adds the interpretive sign. The C.P., meanwhile, filled the ravine with earth dug out of the hill. In the end, the fill won out over the rickety trestle, which was dismantled soon after.

Today, you can drive, walk, or ride on these grades and see this “Big Fill” and the remnants of the “Big Trestle.” I could see the ramparts of the Big Trestle and the grade clinging to the mountainside. Up the hill, there were huge cuts through the mountain, with the excavated boulders stacked nearly on the edge of the troughs.

It was quite a climb for us, too. Juliet admirably attacked the road, much steeper than the railroad grades, but then succumbed to the support vehicle. She was waiting for me at the crest of the hill, where we looked down below us. Promontory was one of the desolate, remote, hidden engines of the West, like South Pass and Glen Canyon Dam. We could see the whole region in that line of the railroad grade in the dry valley, down to the bustling North Temple Station surrounded by construction cranes.

We rode the last few miles through the valley. We crested the last small hill, and there it was. We could see the two locomotives nose to nose, the two little engines in the huge valley. We were at the top and felt the connection to the east and to the west. The place made sense.

Participating in History

In advance of the anniversary ceremony the next morning, we camped at Kosmo, an early 20th century potash mining camp on the north shore of the Great Salt Lake and the C.P. railroad grade. Like Midway, this was a place that I could scarcely believe had been a community, but 200 people once called it home. The remnants of a pier ran out into the playa, and Juliet and I rode our bikes through the rotted posts like a slalom course. The bright sun of the day had turned to storms visible across the lake. Overnight, fine, white sand whipped under our rainfly and through the mesh of our tent.

In the morning, after pancakes and bacon from Earland’s Meats in Tremonton, we made our way back to Promontory. A small town’s worth of people had filled up the parking lot of the Golden Spike Visitor Center. Never having met a gift shop she didn’t like, Juliet navigated the swarms of people and selected one replica golden spike for herself and one for her little brother.

When I saw the locomotives set out on the tracks, I understood what the man at The Pie Dump had meant about their colors — the Jupiter and No. 119 shone in handsome black, red, blue and gold. The Bear River High School band played on one side of the stage. I thought I could pick out the men set to play Durant, Dodge and Stanford.

My great-great-great-great grandfather had been there too. As the book Brother Brigham Holds the Whip recounts, the Union Pacific paymaster, O.C. Smith, noted that on this “clear, cool, beautiful day,” he and his wife rode up to Promontory Summit to “see the last rail laid that connects the Union Pacific and Central Pacific RRds. A large crowd was there.” They stayed until 2 p.m., returning on the first train back to Echo. So — probably not in the champagne photo, but with a good seat in the bleachers.

Walking up to the locomotives, hissing with steam, Juliet approached a man with a white beard alighting the engine in period costume and informed him that her great-great-great-great-great grandfather had been the paymaster for the Union Pacific.

“Well,” he said, chuckling. “That must have been an easy job. Old Doc Durant never paid anyone.”

The re-enactment proceeded. True to this deeply parsed history, Stanford missed the spike. The last spike was actually an iron one wrapped in telegraph wire, heard around the nation.

“Bulletin! From Promontory to the country,” the man playing the telegraph operator announced. The fire alarms in San Francisco and the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia had been ready. And then the final word signifying the completion of this, and the crowd chanted with him — “D! O! N! E! Done!