A Path Through the Canyons

Connecting with an ancient people in an unforgiving landscape

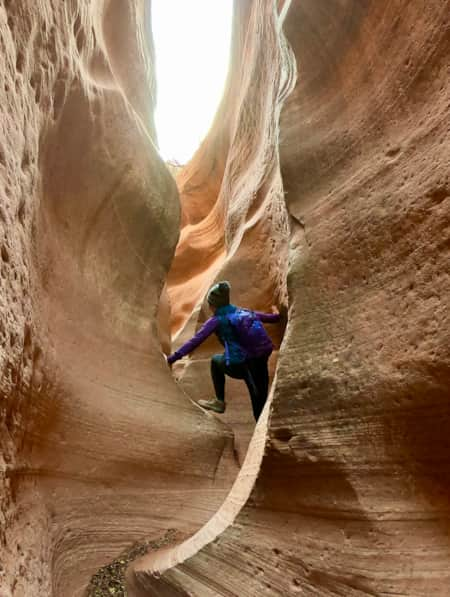

Peering over the edge of a vertiginous slot canyon in Robbers Roost, my mind was seized by the image of a man.

His age, height and posture were similar to mine. And his only objective at that particular moment was to bring food to his family. First, though, he must traverse this canyon. How — in the name of whichever god (or gods) he happened to worship — was he going to manage that?

The man I’m describing was probably a figment of my sun-ravaged imagination. But one might also argue that he was real. After all, human beings have inhabited this desert region for 12,000 years. How many had sought a safe path through this steep ravine? How many had scanned these canyon walls with fear and wonder, just as I was doing now?

I was in Robbers Roost on a canyoneering tour; my second visit to Utah. I knew practically nothing about the ancient inhabitants of this beautiful place. So I decided to ask my guide, Christopher Hagedorn, for a little prehistorical background. Hagedorn — owner of Get In The Wild Adventures — was well qualified to talk about Robbers Roost; he’d been exploring the region for twenty-five years. (Watch the video: Permit of Solitude)

“Back in the Seventies,” he told me, “the Bureau of Land Management did a survey. They found about twenty-four archaeological sites per square mile in this area.”

“We know that these ancient people were very competent climbers, simply by the location of some of their cliff dwellings,” he said.

But who were “these ancient people”? And how did they move through this unforgiving landscape without the help of harnesses and carabiners? More to the point, why did they come here at all? Why not avoid this arid region altogether? On my return to Los Angeles, I arranged a phone interview with Elizabeth Hora, Utah’s public archaeologist, to find out more about these mysterious desert dwellers.

"'Back in the Seventies,' he told me, 'the Bureau of Land Management did a survey. They found about twenty-four archeological sites per square mile in this area.'"

“The Paleo Indians lived here about 12,000 years ago,” she told me. “They were followed by the Archaic People, who inhabited the area from around 9000 B.C. to 0 A.D., and the Ancestral Puebloans, who were here from about 0 A.D. to 1300 A.D.”

I took the opportunity to tell Elizabeth about my experience in the desert; how I seemed to feel the presence of a man who looked very much like myself. I was a little sheepish about this. After all, Elizabeth was an expert. I was not. Perhaps she would think I was ridiculous.

Instead, she sounded intrigued. “Ethologists have a word for that,” she told me. “It’s called ‘umwelt’. That’s the sense of inhabiting a similarly equipped body. We have the same eyes, the same hands, and we’re roughly the same size as another human being.”

“When you’re hiking through a slot canyon, and you scratch your knuckles across the rock, that’s the same experience someone might have had ten thousand years ago. What’s different is your own cultural spin on that experience.”

“I mean, when you see a cottonwood tree you might think: ‘oh man, my allergies are acting up.’ But when a Paleo Indian saw one, he might’ve felt happy because he knew that there was water under that tree.”

So perhaps there was a scientific basis to my flight of fantasy. (At least, that’s how I chose to interpret Elizabeth’s answer!). But how did Paleo Indians, Archaic people and Ancestral Puebloans move through the canyons? Were they using ropes as I did on my trip to Robbers Roost?

"'Ethologists have a word for that,' she told me. 'It’s called ‘umwelt’. That’s the sense of inhabiting a similarly equipped body. We have the same eyes, the same hands, and we’re roughly the same size as another human being.' "

Christopher Hagedorn, guide and owner of Get In The Wild Adventures.

Be aware of your personal skill set and limitations as well as those of your group.

“Most of the ropes we find are thinner than the type you would use to climb with,” said Elizabeth. “But the Ancestral Puebloans were definitely using ladders to assist them. And climbing, of course. We also find hand and footholds hewn into the rock. Those would’ve certainly eased their passage through the canyons.”

“We don’t think that recreation was their objective, like modern-day canyoneering,” she continued. “Canyons were more of a thoroughfare; an obstacle you had to get through.”

But why did they have to get through them? Why were they here at all?

“Most of these people were semi-nomadic: foraging and following seasonal patterns of plants and animals — for sustenance, but also for medicine,” she said. “They also relied on trade.”

“In the 1100s, there was a network of so-called ‘Chacoan Roads’ leading through the desert in southeastern Utah to northwestern New Mexico,” she continued. “These people were mobile in ways that we aren’t today. There’s no reason to think that they wouldn’t hike as far as Idaho, California or even Mexico.”

In that case, it made perfect sense that they would need to pass through this desert. But why choose to live here? Why build homes in such an unforgiving and largely waterless place?

“We think that these high cliff dwellings are evidence that there was conflict between communities,” said Elizabeth. “They were a pretty effective way of guarding against raids. That may be why we don’t see many river dwellings during this period. They were just too exposed and vulnerable to attack.”

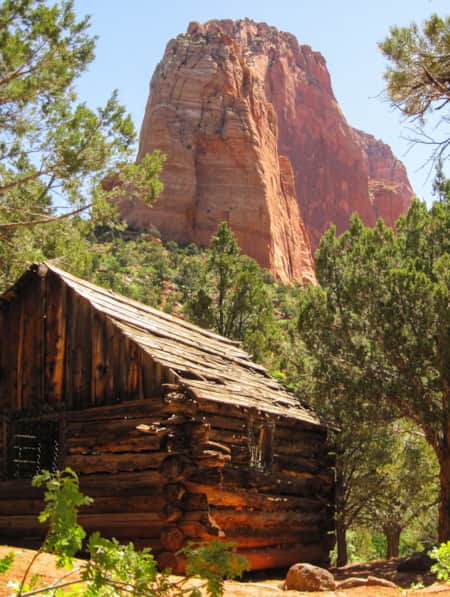

According to Elizabeth, the cliff dwellings (like the ones in Utah’s Nine Mile Canyon or Cedar Mesa and the Bears Ears National Monument) were also vital for food storage.

“You put your granaries high up so other people couldn’t get to them. And if they did, you could be on the ground waiting for them,” she told me.

“This also guards against that lazy family member who never does anything. Imagine you’re a 35-year old Ancestral Puebloan. It’s 4:15 in the afternoon, it’s hot and miserable, and you’ve got to start dinner. You’re not walking up that ladder. You’re sending your kid up there.”

I can certainly relate to this. I often find myself coercing “lazy family members” into preparing meals.

In any case, Elizabeth had opened my eyes. It seemed that these desert dwellers were accomplished travelers, athletes and artists, with trading networks that probably stretched for thousands of miles.

As Stephen Hekson states in “A History Of The Ancient Southwest”: “I want to shift the burden of proof from the current default that ancient Indians were ignorant hicks who knew little or nothing beyond their front yards, or at best their valleys.”

Perhaps the man I pictured in that Robbers Roost canyon was on his way to some faraway place in Idaho or California. I can only hope he made it there safely — and that his family was kind enough to prepare his dinner after such a long and perilous journey.

Follow guide Chris Hagedorn into Robbers Roost in our accompanying video, “Permit of Solitude" and don't go canyoneering with reading our expert safety tips.

Be Prepared

Southern Utah is one of the best areas in the world for canyoneering in slot canyons, but it requires planning and technical expertise to stay safe. Watch our Canyoneering How-to video